The NYT article Drowning Is No. 1 Killer of Young Children. U.S. Efforts to Fix It Are Lagging (7/8/2023) provides data on drownings* that could use some context while also making this statement:

An analysis by the C.D.C. shows that Black children between ages 5 and 9 are 2.6 times more likely to drown in swimming pools than white children, and those between ages 10 and 14 are 3.6 times more likely to drown. Disparities are also present in most age groups for Asian and Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and Native American and Alaska Native children.

It is unquestionably true that the majority of drownings are preventable and worthy of reduction efforts. I support funding so that all children can learn to swim. On the other hand, a cursory reading of the article may lead to misinterpretations and the above quotation appears to be an obligatory NYT insinuation of systemic racism, as clarified by the statement:

Black adults in particular report having had negative experiences around water, with familial anecdotes of being banned from public beaches during Jim Crow-era segregation and brutalized during the integration of public pools.

It is not surprising that the example is cherry-picked and questionable at best. Let's contextualize drowning. Since the article did so, I will concentrate on data for Black and White youths.

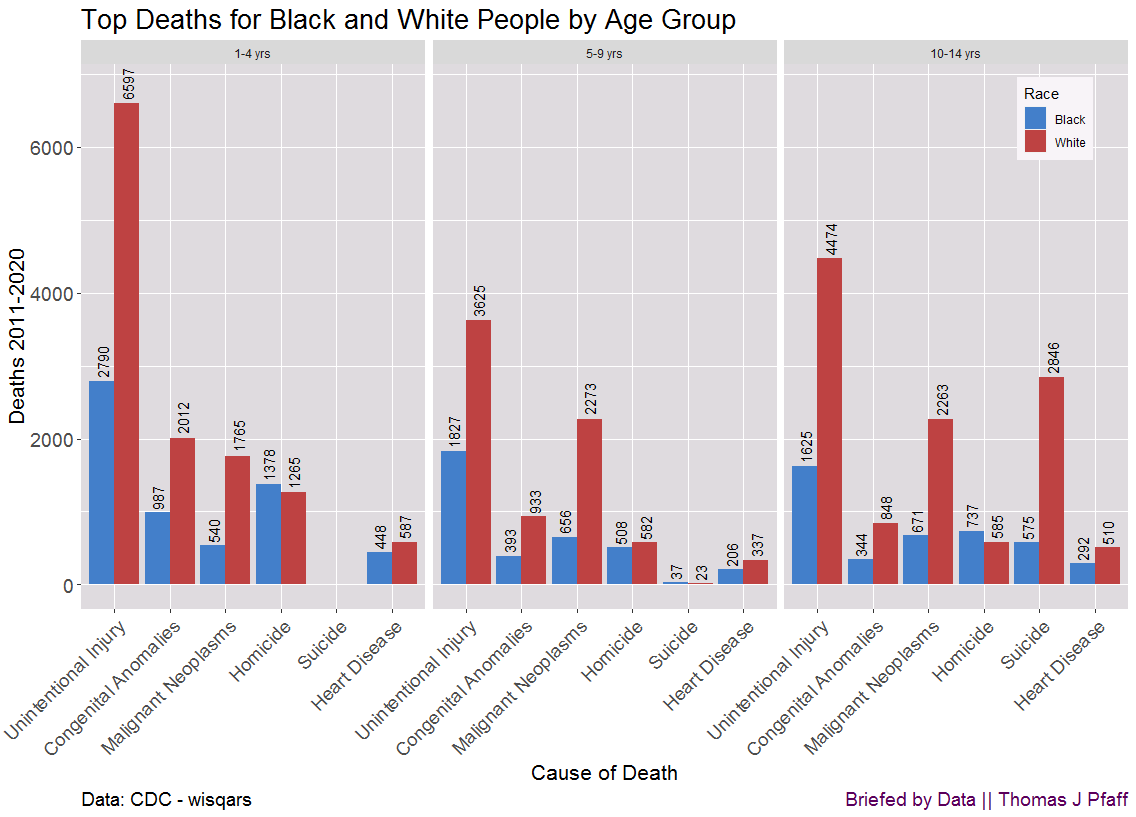

Figure 1 depicts the leading causes of mortality among Black and White youths. Drownings are concealed within the category of unintentional injuries. It is unclear what time period the article references. I selected the most recent decade of data from the CDC. This makes it simple to divide by 10 to estimate the annual value. Also observe that there are approximately 3.6 White youths for every Black youth in these age groups (see U.S. Demographics by Age). To determine if the categories are proportional, divide the number of White deaths by 3.6 and then determine if the number of Black deaths is above or below this value. For instance, in the 1 to 4 age group, there are 6597 unintentional injury fatalities among White children compared to 2790 among Black children. In other terms, there are 1.46 times more unintentional injury deaths among Black children aged 1 to 4 (1919 * 1.46 = 2790) then expected.

In fact, a disproportionate number of Black fatalities occur in nearly all categories, but this does not indicate racism. There are two instances in which there are a disproportionate number of Black deaths: homicides for 1 to 4 years and 10 to 14 years. On the other hand, Black suicide fatalities in the 10–14 age group are underrepresented compared to White suicide deaths. The expected number of Black suicide fatalities would be 790, but there have only been 575. Differences exist for a variety of reasons.

As shown in Figure 2, the death rate significantly increases after the age of 15, putting juvenile mortality into perspective. Noting that this is a 10-year range, divide by 2 in order to compare to Figure 1. There are more unintentional fatalities among those aged 15–24 than those aged 1–14. Also observe that Black unintentional deaths and suicides are below proportional (use 3.7 for this age range). On the other hand, Black homicide is over 4 times greater. Again, the point is that all of this can't simply be explained as racism.

Figure 3 displays the top four categories of unintentional deaths for children aged 5 to 9 by race and sex. Although drowning is the leading cause of death for children ages 1 to 4, motor vehicle traffic accidents are the leading cause of death for ages 5 to 9. This is not surprising given the increased time spent in vehicles and crossing busy streets. In other words, there is much greater opportunity to die related to a car then in water.

It is also not surprising that male deaths are higher, and more so in situations where behavior may be implicated, such as drowning, than in motor vehicle traffic accidents (males do not yet have driver's licenses). The New York Times article mentions demographic differences but not sex disparities.

Figure 4 is the last graph to focus on the context of drownings. Remember that this is over a 10-year span. Annually, drowning fatalities are grossly disproportionately represented. It is fascinating to note that Black children are more likely to drown in a swimming pool, while White children are more likely to drown in natural water, which is not surprising given that the Black population is more concentrated in urban areas.

Let’s go back to the first part of the NYT quote:

An analysis by the C.D.C. shows that Black children between ages 5 and 9 are 2.6 times more likely to drown in swimming pools than white children,

The quotation chooses swimming pools with great caution. Why is the category of swimming pools so important? It is difficult not to believe that it was chosen due to the larger difference. Where did the number 2.6 originate? I do not believe it is proportional; it is merely more. They likely used a different time frame but during the past decade, there have been 254 Black swimming pool drownings compared to 186 White swimming pool drownings, or approximately 1.4 times more Black drownings. Compared to Whites, the proportion of swimming pool drownings for Blacks is five times higher than expected.

There are two major concerns related to the NYT quote. First, the annual quantity is small. A few fewer drownings per year for either group drastically alters the ratios. More importantly, as previously mentioned with regard to motor vehicle-related fatalities, what is each group's possibility of drowning? Do Black adolescents spend more time swimming than their White counterparts? If so, there would be a greater likelihood of fatalities.

As another example, male drowning and submersion following a fall into natural water is proportional (32/3.6=8.9). What does this mean? Nothing. The sample size is insufficient, and we have no notion about the likelihood of this type of accident by race or at all.

Drowning deaths are typically preventable. It is an important topic, but the New York Times did not need to make it a race issue. If it were necessary, they would be forthright about not knowing the likelihood of fatalities and acknowledge the small numbers. In other words, reporting should be more accurate and nuanced. The article does bring up socioeconomics:

Socioeconomic factors are at play as well. A study of drownings in Harris County, Texas, for example, showed that they were almost three times more likely for a child in a multifamily home than in a single-family residence, and that drownings in multifamily swimming pools — like the one at the Salcedos’ apartment — were 28 times more likely than in single-family pools.

I believe it would be more inclusive and simpler to garner support for funding for, say, swim lessons and additional lifeguards if the focus was on socioeconomic factors rather than a questionable race angle.

*Note: The common use of the word drowning is someone dies under water. This is not the CDC definition. “Drowning is the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion or immersion in liquid. Drowning is not always fatal.” They distinguish between fatal and nonfatal drowning. In this article drowning refers to fatal drowning.

Please Share

Share this post with your friends (or those who aren't friends of yours) and on social media to help get the word out about Briefed by Data. You may follow me on Twitter at BriefedByData. Send me an email at briefedbydata@substack.com if you have any suggestions for articles, comments, or thoughts. Thanks. Cheers, Tom.

Data

CDC WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System)