CO2 emissions are an inequality problem

The bottom 60% don't have much energy-related CO2 to cut

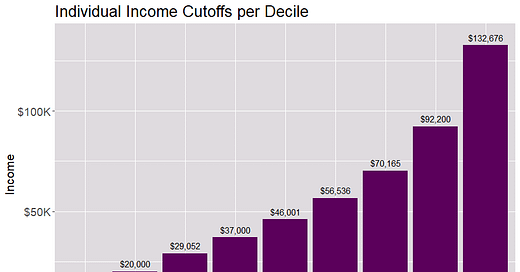

Let's begin with a quiz question. What decile of US income do you believe you are in based on your individual annual income? In other words, is your income in the top 10%, the 40–49% bracket, and so on? Now examine Figure 1 to check if you are correct. Figure 1 is for 2022 and does not take into account your local cost of living. Still, I believe you overestimated your decile rank. I believe that most wealthy people, both in the United States and around the world, underestimate their income rank. My opinion is that if you're reading this, you're probably in the top 30–40% of earners. What follows from the IEA is something that wealthier people don't want to hear, which is that they vastly overemit C02.

The IEA article The world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1% shows that there are large inequalities in CO2 emissions. Starting with Figure 2, we can observe that the top 10% of energy-related CO2 emitters in the world account for 48% of total CO2. The following two deciles release 19% and 13% of CO2, respectively. The bottom 70% account for 20% of CO2 emissions. In other words, if you want to cut CO2, you must concentrate on the top 20–30% of emitters, who also happen to be the highest income earners, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows CO2 emissions per person by income deciles. I'm going to concentrate on the United States, although the dynamics are very much the same in the other countries listed. The top income decile emits 34% of energy-related CO2, and when we include the next decile, 17%, we see that the top 20% of earners emit more than 50% of the energy-related CO2. The lowest 50% of earners are responsible for 19% of all CO2 emissions, the lowest 60% are responsible for 27%, and the lowest 70% are responsible for 36%. In other words, the bottom 70% of earners emit about 1/3 of the energy-related CO2.

The median annual salary is approximately $46,000, which equates to a wage of $22 per hour. To put it another way, fifty percent of the wage earners bring in less than $22 an hour. They don't have enough money to buy a new electric car; they don't own numerous homes or fly frequently. Individually, they do not consume much energy; they do not have much CO2 to reduce and cannot lower it. In fact, we may say the same thing regarding the next deciles. Only when we reach the top few deciles will there be enough CO2 to cut and enough money to do so. According to the IEA:

If the top 10% of emitters globally maintain their current emissions levels from now onwards, they alone will exceed the remaining carbon budget in the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario by the year 2046. In other words, substantial and rapid action by the richest 10% is essential to decarbonise fast enough to keep 1.5°C warming in sight.

Of course, because the top 10% of the globe emits almost half of all energy-related CO2, this statement also implies that if the bottom 90% cannot make significant cuts, we will fall short of the 1.5°C target. Just as there are tensions between China and the United States about emissions, the United States has far greater per capita emissions, but China has more people and emits more CO2. So, who should cut and how much? In the United States, we have the same issues with rich and poor people. Who should reduce CO2 emissions, and by how much?

To put it another way, if the top 10% decreased their CO2 emissions to the level of the next 10%, they would save 30t per person, which is just 2t less than what the lowest 50% currently emits. What should we expect the rest of the population to do if the wealthy aren't going to make significant lifestyle changes?

This is yet another reason why I don't think much will change. The wealthy are uninterested in changing their lifestyles to lower their energy consumption. They may invest some money in electric cars or solar panels, but decreasing consumption is largely out of the question. So, the next time you see a climate activist blocking traffic or doing something similar, remember that the people they are holding up aren't in a position to do much, and they shouldn't necessarily if the top 20% of the income bracket aren't willing to do much either. We've reached an impasse. Either a technological breakthrough or structural changes in society are required to address CO2 emissions. Betting on the latter appears to be a bad bet.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.

The environmental Kuznets curve suggests emissions per capita increases with income, up to a point. Then emissions per capita begin to decline with further increases in income. This theory has supported and also rejected using international data for entire nations. I've not seen a study using income deciles within a nation. I guess it's hard (impossible) to measure emissions per capita in each decile.