It really is blatantly obvious when folks are pushing a narrative and don’t even try to balance their perspective. When your Substack is titled The Climate Brink, well, that's an obvious signal. A recent post at The Climate Brink is How climate change is raising your electricity bill (5/6/2025), which seems innocent enough until you start to read a little further and think a bit, as it is more about pushing a narrative than not.

There are two key issues here. The subtitle “a case study of Texas's electricity market” alludes to the first issue. This is an article only about electricity bills in Texas, which makes the main title misleading at best.

The key conclusion is this:

This post explains the method behind that analysis and why I estimate that climate change added about $80 to electricity costs for every Texan in 2023.

Once more, it appears harmless enough, but it ignores the fact that heating costs, which decrease as the climate warms, are primarily derived from fossil fuels like gas and oil and will not be reflected in an electricity bill. Electricity usage goes up for cooling but doesn’t change much with a reduced need for heating. The compounding problem here is that warming may actually increase the need for cooling in Texas while not reducing the need for heating much. Texas is a wonderful case study if you want a particular result. Let’s go to the data and find out why.

This brings us to the notion of degree days to help us understand regional differences in a warming climate. For a given day, heating is the difference between the average temperature for the day (the max plus min temperature divided by 2) and 65°F, when the mean is below 65°F. Add up all the heating degree days to get the total heating degree days for a year.

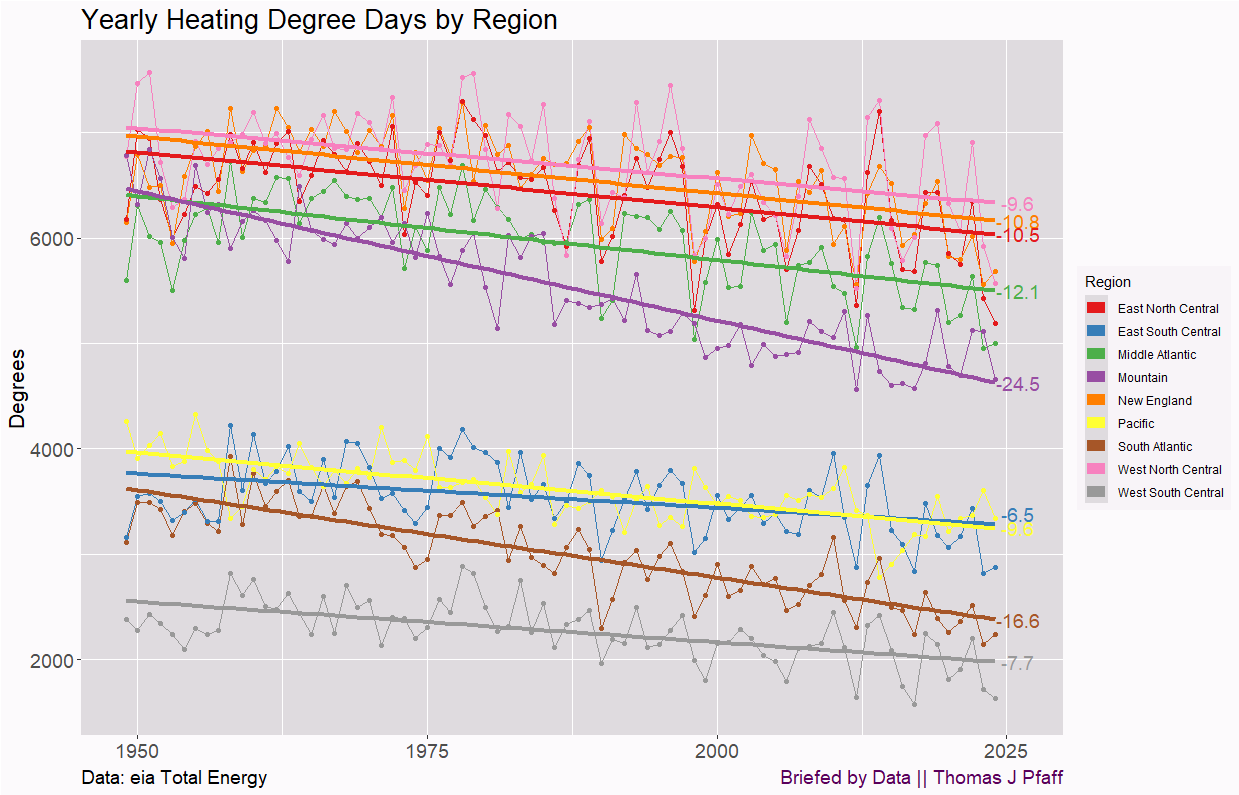

Figure 1 is the annual heating degree days from the eia by census divisions (see Figure 2). The graph includes regression lines for each region. The values at the end of the lines are the slopes in units of degree days per year.

Texas is located in the West South Central division, as indicated by the gray data. Notice that not only did that division’s heating degree days start at the lowest amount, but they also decreased the second least. But it still decreased, and so consumers in Texas would be spending less on heating in 2023. In other words, the $80, which isn’t exactly an exorbitant cost of climate change, is an overestimate since it is only electricity for cooling due to climate change and isn’t adjusted downward for the reduced heating cost.

The Mountain Division (purple), on the other hand, is spending much less on heating “thanks” to climate change.

Heating degree days is a useful proxy for heating costs. We tend to start heating right below 65°F. Cooling degree days, which is the amount the average temperature is above 65°F, is not as good of a proxy for cooling costs because people don’t cool their homes until it is much warmer than 65°F. Still, let’s look at yearly cooling degree days in Figure 3.

One big caution in comparing Figures 1 and 3. Cooling is more energy intensive than heating, and so we can’t make one-to-one comparisons between heating degree days and cooling degree days.

Still, the West South Central division already had the highest cooling degree days, by far, and was third in the rate of increase of cooling degree days. The Climate Brink article's use of Texas as a case study might be the worst-case scenario for increases due to cooling. The article ignored the cost savings for heating and used a state that was already warm and got warmer faster than most. Yes, your cooling costs in Texas are going to go up. In fact, $80 per year isn’t that bad, all things considered.

The Mountain Division had the highest increase in cooling degree days, but as I noted above, that might not have translated into much of a need for cooling, and the increase in cooling degree days rate of 11.6 degrees per year is less than half of the decrease in heating degree days rate of 24.5 degrees per year. It is highly likely that those living in the Mountain Division are saving money due to climate change.

My experience in the Middle Atlantic Division (green line in both graphs) is that while we need a little extra cooling in the summer, the need for heating has decreased noticeably, partly due to minimum temperatures at night warming faster than even daytime temperatures in the winter. So far, climate change is a win on utility bills.

My point here is not to minimize the seriousness of climate change. It is serious even though I don’t think we are or will do much about it. At the same time, articles like the one in the Climate Brink, along with the related peer-reviewed paper, are highly misleading and slanted. They only considered electricity expenses, which ignores savings from reduced heating needs, and used a state that provides a result they would like to see, but what do you expect from a place called The Climate Brink?

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. Please feel free to share article ideas, feedback, or any other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD in Math: Stochastic Processes, MS in Applied Statistics, MS in Math, BS in Math, BS in Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations.