The good folks at MIT have a study (June 2025) looking at the impacts of using ChatGPT on the brain. Disclaimers: This is a small study that has yet to be peer-reviewed. The results aren’t surprising, as having AI do your work takes less brainpower than doing it yourself.

We discovered a consistent homogeneity across the Named Entities Recognition (NERs), n-grams, ontology of topics within each group. EEG analysis presented robust evidence that LLM, Search Engine and Brain-only groups had significantly different neural connectivity patterns, reflecting divergent cognitive strategies. Brain connectivity systematically scaled down with the amount of external support: the Brain‑only group exhibited the strongest, widest‑ranging networks, Search Engine group showed intermediate engagement, and LLM assistance elicited the weakest overall coupling. In session 4, LLM-to-Brain participants showed weaker neural connectivity and under-engagement of alpha and beta networks; and the Brain-to-LLM participants demonstrated higher memory recall, and re‑engagement of widespread occipito-parietal and prefrontal nodes, likely supporting the visual processing, similar to the one frequently perceived in the Search Engine group. The reported ownership of LLM group's essays in the interviews was low. The Search Engine group had strong ownership, but lesser than the Brain-only group. The LLM group also fell behind in their ability to quote from the essays they wrote just minutes prior.

Tyler Cowen, who I believe generally does great work but misses the point here, published an article at The Free Press following this announcement. Tyler Cowen: Does AI Make Us Stupid? (6/23/2025). His main point is that while AI is easier, it's also important to measure how you use the extra time.

The important concept here is one of comparative advantage, namely, doing what one does best or enjoys the most. Most forms of information technology, including LLMs, allow us to reallocate our mental energies as we prefer. If you use an LLM to diagnose the health of your dog (as my wife and I have done), that frees up time to ponder work and other family matters more productively. It saved us a trip to the vet. Similarly, I look forward to an LLM that does my taxes for me, as it would allow me to do more podcasting.

This is a fair point, and Tyler gives a list of things he would do:

They can ask it to criticize their work, as indeed I have done with this column. They can argue and debate with it, or they can use it to learn which books to read or which medieval church to visit, as indeed I am doing on my current travels in Spain and France. They can ask it to give the history and background on each church, as I also am doing. I learned, for instance, how the church in Reims, France, brought in Marc Chagall and later the German artist Imi Knoebel to help spruce up the presentation in previously damaged windows.

I have two issues with his argument. First, he uses himself as an example. The main issue is that individuals with excessive education do not even remotely accurately represent the general population. We are outliers and oddballs.

I shake my head every time I hear a faculty member complain about students with “When I was in college…,” yeah, you likely weren’t a typical college student (I have a second BS because I was closer to a normal college student the first 4 years; I’m not giving details).

The second problem here is that there is data that can give us an indication of what people might do with their spare time: the BLS America Time Use Survey (ATUS). The ATUS doesn’t specifically track social media or digital media use, but according to Our World in Data, by 2018, the average digital media use was 6 hours a day.

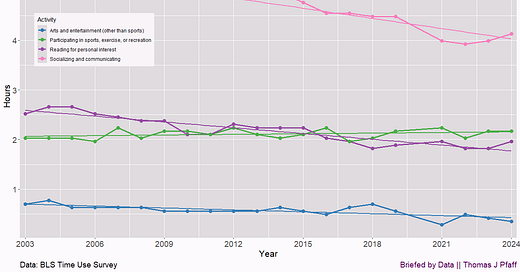

As social and digital media, along with smartphones, have captured our attention, here are some examples of changes observed in the ATUS data.

In Figure 1, we see that from 2003 to 2024, socializing has decreased by about 1.5 hours, reading for interest is down about half an hour, and arts is down about 20 minutes a week. Interestingly, participating in sports or exercising takes about 10–15 minutes a week.

Before I focus on reading, I want to note two other activities shown in Figure 2. TV watching averages about 17 hours per week; although it has decreased slightly over the past few years, the overall trend remains upward. Meanwhile, the average time spent playing games has increased by a couple of hours per week.

If people wanted to read more, visit art museums, or have AI tell them “which books to read,” they have the time, as cutting an hour or two a week of TV wouldn’t be that hard. Do we really believe that using AI to free up time will lead to a renaissance of reading and the arts? I don’t.

The graphs above are an average of those surveyed, and for activities such as reading, there are lots of 0 hours a week. One possible explanation for the decline in reading time is that either fewer people are reading, there are more zeros, or everyone is reading a little less. Let’s look further at the reading data. Figure 3 shows the percentage of people who read.

The percentage of women that read has dropped from about 29% to 18% from 2003 to 2024. The percentage of men who read has also decreased, but the decline is smaller than that of women. Still, reading has declined substantially.

Of those who do, how much do they read? Figure 4 shows that this has gone up. While both men and women read more on average, for those that read, men have closed the gap with women. I suspect what is happening here is those that read only a little have dropped out, allowing the mean to go up.

There are other intellectual pursuits beyond reading, but reading is a good proxy. Certainly Tyler Cowen reads a lot. The evidence that using AI to “do my taxes” is going to lead to the average person doing other intellectual activities is dubious at best.

I’ve said this before: AI is going to make smart people smarter and dumb people dumber. People like Tyler will use AI to free up time for engaging in other intellectual tasks that stimulate their minds, but evidence suggests that most people will instead spend more time scrolling on their phones or binging more shows.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please tell me if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. I encourage you to share article ideas, feedback, or any other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD in Math: Stochastic Processes, MS in Applied Statistics, MS in Math, BS in Math, BS in Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations, and I’m open to job offers.

The legal work stuff was just to illustrate my point. I can only estimate as an outsider on how the legal profession will change in the long run as LLMs take over.

As far the research on LLM use in productivity goes, the mostly consistent finding is that low skill workers benefit the most and they can use it to catch up with high skill workers. LLM use didn't seem to benefit high skill workers as much suggesting that high skilled workers are the ones who're the mostly likely to lose in the adoption of AI.

I'm probably more on the Tyler cowen camp.

I wrote a short note about the potential impact on the labour market. We mostly use our brain powers for job stuff instead of intellectual pursuits. The job market impact is more relevant for most people.

https://substack.com/@mdnadimahmed888222/note/c-131001514?r=o2bbq