I’ve talked about the fact that poorer countries rightfully want to have a standard of living similar to wealthy countries like the USA. This is a real challenge to reducing fossil fuel use because if one country adds solar panels, some other country will gladly use their fossil fuels to generate electricity. Robet Bryce (his substack is excellent) added context to this with an excellent talk at ARC (Alliance for Responsible Citizenship). It is under 12 minutes long, adds a human element to this, especially as electricity impacts women, and it is worth watching. His chart on the money in activism is also enlightening. After the video, I have charts on country electricity use per capita.

Figure 1 is 2023 per capita energy generation for 95 countries. There is a close relationship between generation and use, so we’ll take this as per capita electricity use. A few caveats when comparing countries, the main one being that electricity use is not the same as energy use. Heating is more often done with fossil fuels, for example. Cooking could be with either gas or electric in wealthy countries and wood, grass, or dung (watch the video) in poor countries. Regardless, more electricity does mean a more comfortable life.

The first thing that jumps out in Figure 1 is how much electricity is used in Iceland (ISL). This is due to industrial use of electricity (aluminum smelters) and that their electricity is almost all from renewable sources. The graph will be easier to read if Iceland is removed. Onto Figure 2.

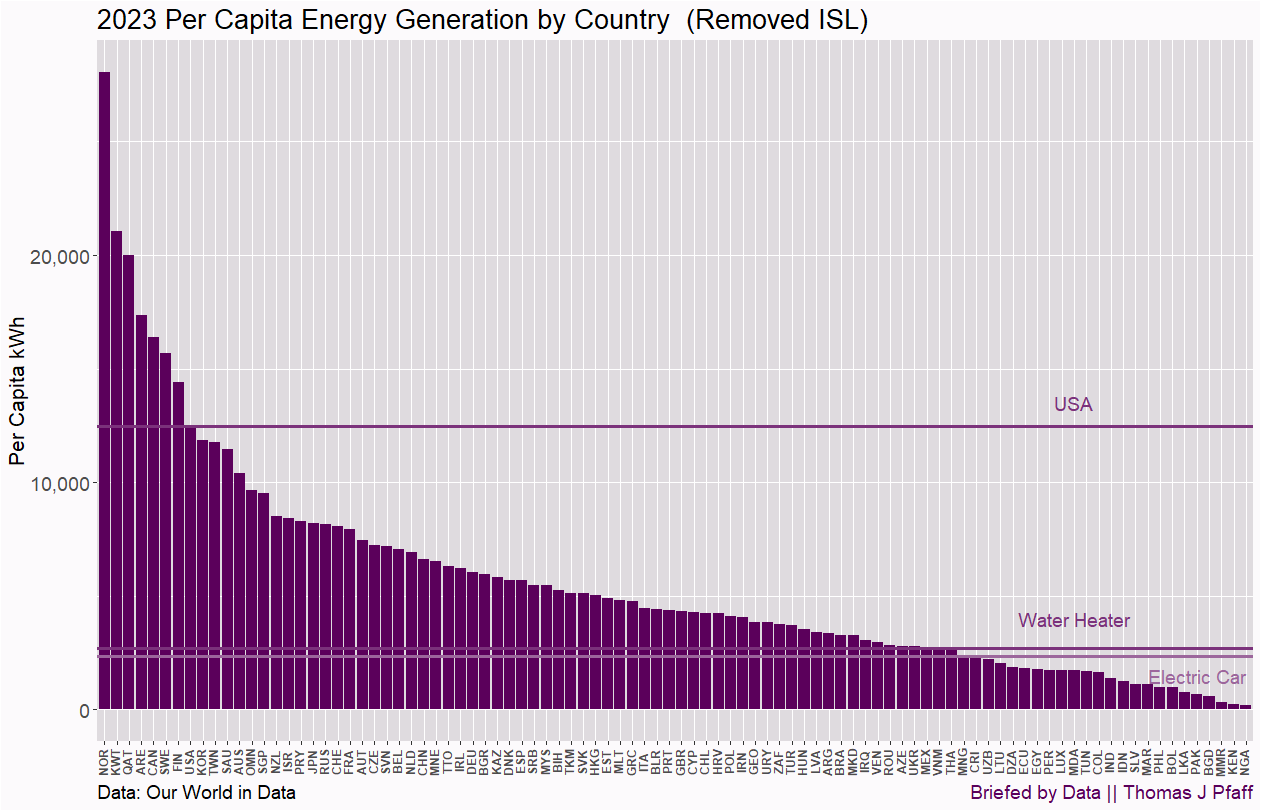

Figure 2 is the same as Figure 1, but with Iceland removed. At the bottom end, 25 countries don’t have enough electricity to have a water heater, and 23 don’t have enough energy for an electric car (2020 estimates from energy.gov). In both cases, this is more than 25% of countries in our data set.

The other obvious fact is how big the gap is between the USA and the rest of the world. Only a few countries use more, and the vast majority use less than half. This would be an enormous amount of energy.

Just to give one example. The USA uses 12,497 kWh per capita, and Mexico uses 2,751 kWh per capita. In 2023, Mexico had 129.7 million people. To get Mexico to the USA would mean (12,397 - 2,751) * 129.7 = 1,251,086 million kWh, or 1,251,086,000,000 kWh, or about a trillion and a quarter kWh. A gigawatt hour is 1,000,000 kWh, and so Mexico would need to add 1,251,086 GWh of electricity. How can this be done?

A power plant with a gigawatt capacity operating continuously would generate 8,760 GWh over a year. Most plants don’t operate continuously, especially wind and solar. We’ll ignore this for now. We would need 1,251,086 / 8,760 = 142.818.

From energy.gov, here we go: Roughly 1,887,000 * 143 = 269,841,000 solar panels, 294 * 143 = 42,042 utility-scale wind turbines, or 103 * 142 = 14,626. Other sources suggest 1*143 = 143 large nuclear power plants (the U.S. currently has 54). Natural gas plants can get to almost 1 gigawatt, so 143 of them would just about do it. For solar and wind, you really need to double or more the numbers since they don’t run all year. The point is it would take a lot just to get Mexico to the U.S. levels of electricity. Now do this for the rest of the world. Oh, and don’t forget to add all the power lines, substations, etc., and a ridiculous amount of battery storage if you want to use only wind and solar. Good luck.

One more point about Figure 2. If you want everyone in the U.S. or, more fairly, every other person to have an electric car, increase the USA bar by half the electric car level. Don’t use that extra generation for the poor countries, just to move the USA to electric cars. Do you consider that fair or not?

Two more graphs, just for fun. In the Our World in Data data set, the first year with most countries is 1998, and so I looked at change from 1998 to 2023. The first, Fiugre 3, includes Iceland, which apparently added an amazing amount of electricity generation over the 25 years. They have unique resources. The second, Figure 4, removes Iceland.

If you are looking for the USA, it is on the right as per capita generation fell by 12,497 kWh per capita. I’m not sure why. Efficieny? Immigration that added low users of electricity? Intersting question.

The key point is that very few countries added enough electricity over 25 years to run a hot water heater or electric car. The majority added 1,000 kWh per person or less, a bit more to run a refrigerator (839 kWh per year) or clothes dryer (680 kWh per year).

All this goes back to my main point. Which is more important, decarbonizing the rich countries while maintaining their standard of living or bringing the poor countries standard of living up? Sure, ideally both, but the first one alone is questionable as renewable energy is largely just adding to usage so far. Meanwhile, life isn’t improving much, if any, in poor countries.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. We should all be forced to express our opinions and change our minds, but we should also know how to respectfully disagree and move on. Send me article ideas, feedback, or other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD Math: Stochastic Processes, MS Applied Statistics, MS Math, BS Math, BS Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations.

Good points Tom and excellent example, Buzen. We have hardly addressed how the WORLD can lower electric use. Economists do not even have a name for how the world can maximize resource use. Microeconomics is about firms and households can maximize resources. Macroeconomics is about how nations can maximize resource use. There is no field in economics about how the Earth can do the same. There is a lot in international economics about customs unions, but it seems like there is not much that can be done, policy-wise, globally.

One reason for the fall in US electricity generation since 1998 is that because of high prices, aluminum refining moved to cheaper countries. Primary aluminum refining went from 3.8 million tons to 750 thousand tons in 2023. In addition to moving to lower cost countries like Canada and China, the US increased use of recycled aluminum which uses much less electricity to produce.

Other industries also improved processes or left for cheaper offshore locations after the 2008 financial crisis.