Interesting state migration patterns

A guest post

Today is a first for Briefed by Data. We have the first guest post, which is from an Ithaca College alum, Drew Erskine. He explains how this came to be below. I’ll be back on Thursday with Quick Takes and Random Stuff. Cheers, Tom.

There are numerous reasons why state-to-state migration is important to consider, including economic impact, labor market alterations, social and cultural changes, and contemporary political and electoral pressures. My purpose here is not to form conclusions about those issues, but to digest the facts and present you with what I believe are intriguing insights, such as why people are leaving Alaska. According to what I've heard, it's an excellent area for fly fishing and the birthplace of ranch dressing!

My name is Drew Erskine, and I work as a forecasting analyst and capacity planner for major call centers around the US. I am also an old Pfaff's student, and I honestly prefer blue cheese to ranch for my wings. I recently contacted Pfaff in search of an interesting side project for my free time. I rarely have time to brief folks on data that isn't call center-related, so to say this was a breath of fresh Alaskan air is an understatement.

I used data from the United States Census Bureau, which asked respondents across the country if they lived in the same state a year ago. For those who had relocated, their previous state of residency was documented.

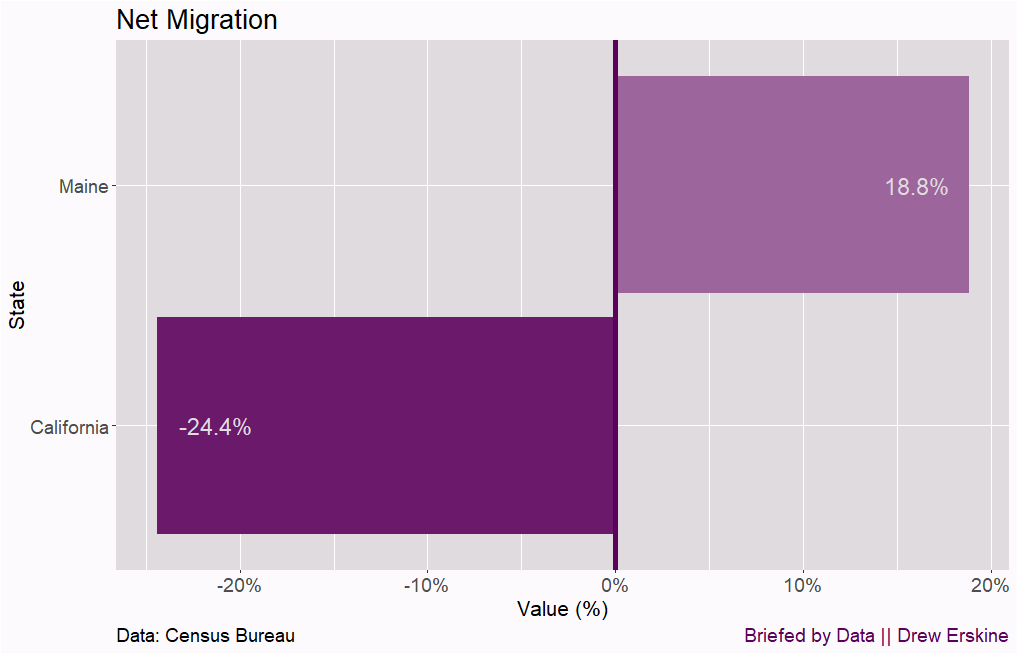

To really grasp how these state-by-state fluctuations occur, we must look beyond simple numbers. For example, how can we compare the extent of migration in a huge state like California to that of my home state, Maine? And how can we determine whether a state is seeing a net inflow or outflow of residents?

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate migration patterns while considering each state's population and showing whether more people moved in or out during 2023. In Figure 1, net migration represents the difference between the number of people moving into a state and the number moving out. A positive net migration means more people are moving into the state, while a negative net migration means more people are leaving. For example, if net migration is 100%, it means that all the people who moved either in or out of Maine ended up moving to Maine. Figure 2, on the other hand, shows the migration rate relative to the state's population, which reflects the total number of people who moved in or out as a percentage of the state's population. For example, in 2023, 5% of Maine's population either moved into or out of the state. Or for those who need the numbers, 64,000 of the 1,200,000 people migrated in or out of Maine.

Let’s take these graphs and combine them to see migration trends for every state and every year from 2010 to 2023, Figure 3.

States farther to the left show higher rates of people leaving, while states farther to the right show people moving in, and moving upward along the Y-axis shows an increase in migration volume relative to the state's population. I added one more variable to this: if the state has more people migrating out on average, it is colored light purple, and if more people are moving in, it is colored dark purple. What's going on in the upper left? That would be Alaska. And the bottom right? Well, half of that is my fault, literally.

In 2021, my wife and I decided to migrate to Maine. Maine had an inflow of migration, with 43,000 (~42%) of the total 61,000 migrants moving there. This was really noticeable during the first few months we lived here. Almost everyone we met seemed to have come from Massachusetts or New York to get away from the hustle and bustle of city life. The Sankey Diagram in Figure 4 depicts the migration into Maine in 2021. This compares the states with the most migrants, top to bottom. The width of the bar also serves to represent this.

As expected, the majority of people arrived from Massachusetts. Unfortunately, we can't say for sure if these people are from Boston, but believe me—they were! What surprised me, however, was that New York did not make the top three. My neighbors and their lively Dalmatian were from Brooklyn, which made me wonder: if New Yorkers aren't coming to Maine—the most magnificent and, frankly, best state—where are they going instead? Why isn't everyone in the U.S. looking to relocate to Maine?

Well, it turns out that no one is migrating to Maine. In fact, none of the top five states with the greatest average departure rates per capita (New York, New Jersey, Illinois, California, and Alaska) went to Maine. I understand that Maine is not for everyone, especially with its lengthy winters, but what can this chord graph, Figure 5, tell us about where people are moving?

In Figure 5, the bottom of the chord graph shows the top 5 states, and the bars extending from each state represent where the people from that state migrated. The size or width of each bar indicates the volume of migration, with wider bars showing larger flows of people.

For starters, people tend to stay in their own region; more importantly, it appears that they move from one state with a significant city to another. Except for Alaska, most of these states have a city that is in the top ten most populous in the United States. Apart from New Jersey, where one might argue that the entire state is a suburb of two big cities (New York City and Philadelphia), all of these states have cities ranked among the top 40. Mind you, this data just shows the state they are moving to, not the city, but it makes you wonder about the migration patterns of large cities.

Now, what's going on in Alaska, and why the mass exodus? From 2010 to 2014 (perhaps later, although our data does not reveal the extent of movement beyond 2010), about a quarter of Alaska's population migrated in or out, with nearly half of those people migrating out. Did anyone foresee anything happening? Perhaps as this article delves into “The Great Alaska Recession” and discusses a recession that began in the summer of 2014. Many things contributed to this recession, but the most significant to me was a decaying pipeline that was flowing at a rate of 660,000 barrels of oil per day in 2010 but was gradually decreasing in flow to the point that the amount was anticipated to be reduced in half by 2022. This would undoubtedly alarm the 13% of Alaskans who work in the oil business. And, given the Alaskan recession article, falling oil prices, and a surge in government job layoffs, I too would prefer to take my abilities somewhere else. This is demonstrated in Figure 6, which illustrates how many people from Alaska moved out and to where during that time period:

States with the * signify that they are among the top ten oil-producing states. 25% of Alaskans who moved between 2010 and 2014 did so to those states, although this ratio rises to 40% if you add states on the Gulf Coast (states with **), i.e., offshore drilling. If the delay in oil production caused individuals to relocate from Alaska and given Briefed by Data's recent piece, “Are EVs Just Gonna Win?” Will there be an upsurge in individuals leaving these states again? I'll let you know in ten years. But, until then, I'd be watching the oil business and how we as a country decide to shift away from a finite source of energy, all while eating my wings with blue cheese.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. Everything you do is appreciated.

Comments

Please point out if you think something was expressed wrongly or misinterpreted. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. We should all be forced to express our opinions and change our minds, but we should also know how to respectfully disagree and move on. Send me article ideas, feedback, or other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Good job, Drew. Fascinating info.

Interesting stuff. Well done. Please tell the migrants from Massachusetts and NY that in Maine we stop for pedestrians in a crosswalk.