Is College Affordable?

A critique of Brookings, part 2.

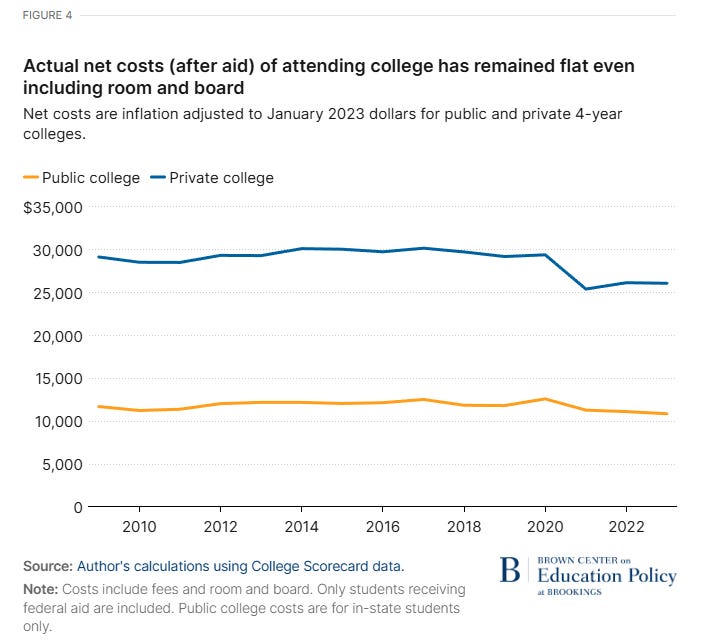

In the Brookings’ article What college affordability debates get wrong on the returns to college (12/16/2025), I’ve already commented on the issue of return on investment for college in Is College Worth It? last week, but there is a second graph in the article that deserves some attention. Let’s get right to it.

The point here is that the net cost of attending college, adjusted for inflation, has remained flat for 15 years. Why is college then perceived as so expensive? The Brookings article states the following:

If the cost of college has been flat for so long, why do so many seem to think the cost has skyrocketed? There is one reason that is understandable. The flat costs are really only true for trends covering the last decade or so. From the 1990s up until the Great Recession, tuition costs increased significantly over and above inflation. In other words, college costs more today than a generation or two ago, which may explain why parents and grandparents perceive it as expensive.

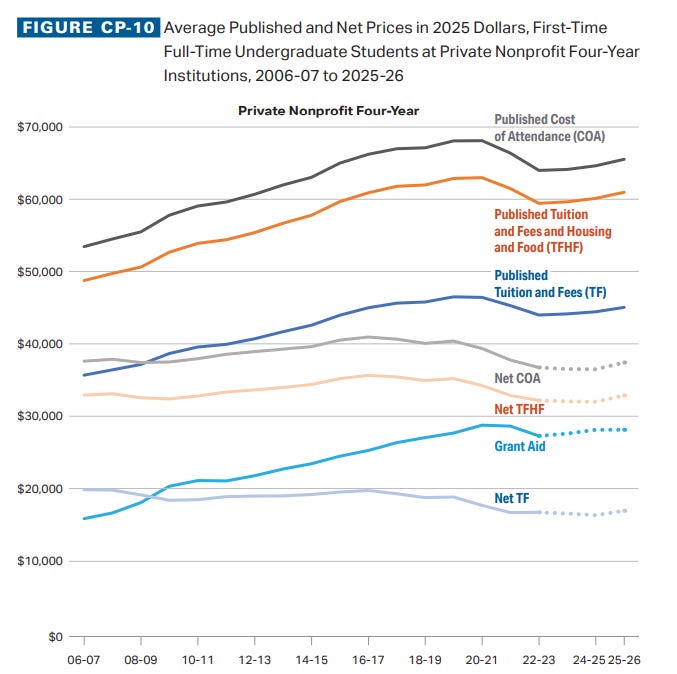

I found this explanation lacking. The link in the quote is for the report, Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2025, by the College Board. Here are two graphs from that report.

The first is for a private nonprofit four-year college. The gray line in the middle of the graph indicates that the net cost of attendance (Net COA), which includes room and board, stopped rising before 2008, increased at a rate faster than inflation throughout the 2010s, and then dropped after COVID, when adjusted for inflation. In 2025, the Net COA is about the same, adjusted for inflation, as in 2006. The net cost has been near flat for two decades.

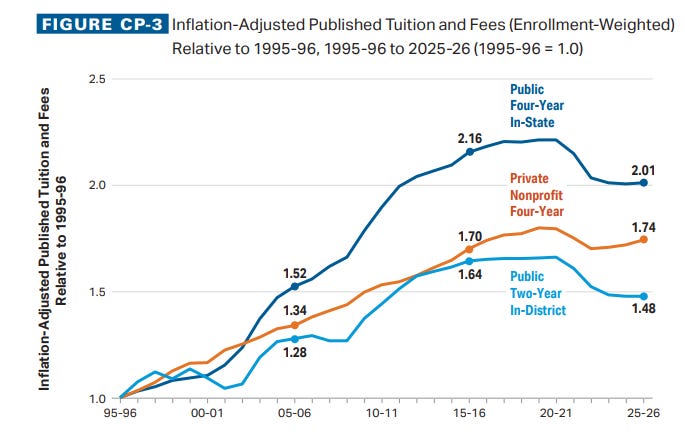

The graph in the report for public four-year colleges is similar. If we look at the graph for published tuition and fees, we have data going back further. Here it is:

The report notes that

The increases in the net prices that students actually pay, after taking grant aid into consideration, have been smaller over the long term than increases in published prices.

But roughly, if the trends for net prices are similar, the cost of a public four-year in-state college roughly doubled relative to inflation from 1995 to 2025. Private nonprofit colleges experienced an increase in tuition and fees that was approximately 75% higher than the rate of inflation. Now, here is the key quote in the College Board report:

Over the 30-year period from 1994 to 2024, median family income in the United States increased by 39% (from $76,170 to $105,800), after adjusting for inflation.

It is really misleading to talk about changes in the costs of tuition without talking about changes in income. The bottom line is that the median family income has not kept up with the rising costs of attending college. The college net cost of attendance has remained flat for a decade or two but still leaves families far behind. The problem isn’t an issue of parents or grandparents simply perceiving “it as expensive.” It is expensive.

An economist can probably say more, but at some point you must reach a tipping point here. When a family's income starts to lag behind tuition increases, you initially cut back on spending. This approach eventually fails, leading families to take out more loans. This probably worked for a while until families started to realize that they were taking on too much debt. Families then begin to seek more affordable options, such as starting at a community college, and start openly discussing the high cost of college. What you end up with is where we are today. Brookings is attempting to argue that college is not very expensive because costs have remained flat for the past decade or two, but it completely overlooks the fact that family income was not keeping pace prior to that period.

I think this is only part of the story. I have an additional point to consider regarding the data rule: Know the distribution, not just the mean and median. We are looking at the median, or average, net cost of attendance in the data above.

Here is one example. Here is the net price based on family income brackets for Providence College. This year Providence is ranked #2 for Northeast University but has a higher sticker price than number #1 Bentley. The posted net cost is $41,767.

If your family income is under $30,000, your net cost is less than half the average net cost at $20,260, and it is still too expensive. A student would need to borrow nearly the entire amount of $20,260. Maybe a job on campus and summer jobs would cut into this, but the family can’t help. At the top of this bracket, the annual cost of Providence is 2/3 of the yearly family income.

When I look at this chart, it would seem that most families, regardless of income, would have difficulties paying the net cost for them. Now, these are averages within brackets, so maybe some folks would find it affordable.

Now, Providence College is an extreme example, so to be fair, here is the same chart for SUNY Geneseo, the highest-ranked four-year state school in the Northeast at #17. This seems more affordable, but $10k is still a lot of money for a family making under $30k, so one would expect that a student in this bracket has $40k in student debt. While the financial burden is still significant, it may not be terrible.

For individuals earning $110,000, the $24,000 amount remains substantial, and it is unclear where these families are residing. If it's in NYC, they likely don’t have a lot of disposable income.

In the end, talking about net costs of attendance on average hides a lot of what is going on. There are differences in net cost based on income brackets, and schools vary in how they allocate their aid. Private schools are expensive; it isn’t just a perception. Public schools are not as pricey, but the cost is still substantial.

I do think one can obtain a college education affordably if they are savvy. One way is to live at home for at least two years and attend a local community college. You can likely do that with no debt and even save some money while working in college. Then transfer to a state college for the last four years, preferably locally so you can continue to live at home. Don’t be fooled by this quote from the Brookings article.

An alternative is to include room and board and books. There are two things to consider with room and board costs. First, these costs are high. Second, these costs are high for all people–and even if a person doesn’t go to college, they still have to eat and live somewhere.

For traditional college-age students, the cost of living and eating at home is considerably less than on campus. The marginal cost to the parents of having a student live at home is small; the cost of living and eating on campus is expensive.

The Brookings article ends with this quote that I don’t think it lived up to.

But we can, and should, have policy discussions that start with accurate information about college costs over time.

On one hand, I would say the data they used is accurate but far too superficial to fully understand the cost and value of college, while entirely ignoring any risk that college might not pay off and not considering other options such as trade school. Hopefully I’ve added some details, but I wouldn’t say I’ve provided all the accurate information for a policy discussion, yet.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please tell me if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. I encourage you to share article ideas, feedback, or any other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD in Math: Stochastic Processes, MS in Applied Statistics, MS in Math, BS in Math, BS in Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations, and I’m open to job offers (a full vita is available on my faculty page).

Nailed it on the median family income point. The flat net cost narrative completely ignores the baseline shift that happend in the 90s and early 2000s. My brother graduated in 2003 and took out way less debt than me for the same degree at the same school, even though "costs were flat" for both of us technically. The income bracket breakdown is crucial too, cause the aggregate numbers hide how regressive the burden actualy is. A 110k family in NYC paying 24k for SUNY Geneseo isn't exactly comfortable, and that's supposed to be the affordable option.

Lots of point estimates all around. When talking about populations, the dispersion is equally important. Maybe some people qualify for discounts (scholarships or whatever), maybe others don't. For the second population the costs are infeasibly large.

The people who can afford college stay quiet, the other group is getting larger in all likelihood.