Reporters are being lazy when they say that discrimination is the main or only cause of racial differences. By doing this, other possible causes of the differences are ignored, and issues don't get solved. Also, article headlines that tell a story about race tend to be divisive and often wrong. In their piece “A critical emergency”: America's Black maternal mortality crisis (7/23/2023), The Guardian does all of this.

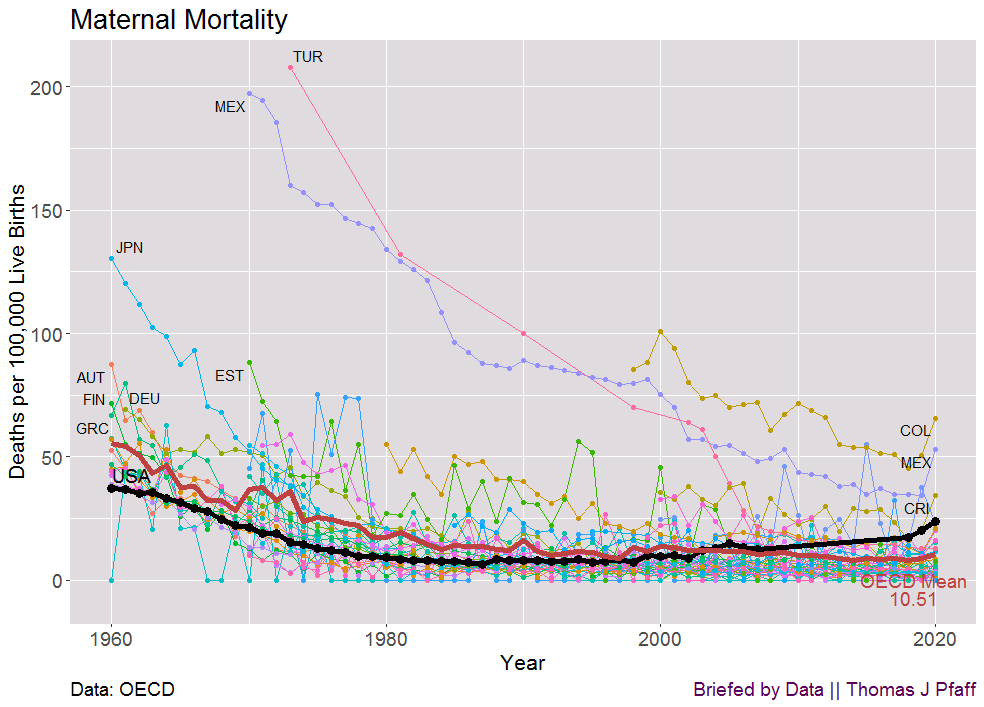

Let's start by being honest about the deaths of mothers. Figure 1 shows the rates of maternal mortality from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 2020, which was the last year for which data was available, the U.S. rate was back to where it was in the late 1960s. In 1960, the U.S. had the best rates, and in 2020, we are almost at the bottom. In fact, the rates of death among mothers in the U.S. have been going up since around 2000. There's something wrong.

Figure 2 shows that there are clear racial differences in the U.S. Figure 2 also shows the year 2021, which is not yet in the OECD statistics. In 2020, the Non-Hispanic White rate was twice as high as the OECD average. Even the lowest group in the U.S. in 2020, Hispanics, were almost twice the OECD mean. It's interesting that the Guardian article doesn't mention Hispanics. Figure 3 also shows the death rates of mothers by age group. The rate of maternal deaths under 25 in the US in 2020 is also higher than the OECE average. The rise in rates among people over 40 is shocking.

Figure 2 shows that there is a racial difference because the Black 2020 rate is more than 2.5 times the White and Hispanic rates. Is this because of racism, especially since the general U.S. maternal mortality rate is so poor?

Kevin Drum has already addressed the question of racism in maternal mortality. In his March 2023 post, he notes

It's not because nobody cares about this. It's getting more study now, but researchers have been trying to puzzle it out for a long time. Nor is the racial gap due to racism—not entirely, anyway. Nor is this upward trend happening in other rich countries. Only in the US. And we've been pulling away from other countries only since 1999.

In his May 2019 lengthy post, which is well worth reading, he summarizes

What we’re left with is this: Poverty, education level, drinking, smoking, and genetic causes don’t seem to explain the black-white difference in maternal mortality. The timing of prenatal care doesn’t explain it. Medically, the cause of the difference appears to be related to the circulatory system, which is sensitive to stress. This makes the toxic stress hypothesis intuitively appealing, but it has little rigorous evidence supporting it.

I'm not going to repeat Drum's case. Instead, a few other things about the Guardian piece should be brought up. The story talks about a report from the CDC that has information from 36 states from 2017 to 2019. There have been 1,018 deaths of mothers. There are 467 non-Hispanic White women deaths, 315 non-Hispanic Black women deaths, and 144 Hispanic women deaths.

The piece in the Guardian is about a woman who was treated badly when she was having her third child. The story was used to demonstrate that there was racism. Most of the time, you shouldn't pay much attention to these one-off stories unless a study shows that they are typical of what really happens. Still, more non-Hispanic White women died than Black women. There are also more White women who are not Hispanic who have babies. How can we be sure that none of their stories are the same? Then, The Guardian says:

Shocking attitudes can still be found in US medicine. A 2016 study on racial pain assessment found 12% of medical students surveyed believe Black people have less sensitive nerve endings and 58% believe Black people have thicker skin than white people.

I don't think the study supports the claim that racism is a main factor in medical care. In short, the study asked 15 true or false questions about how Black people are different from White people. For example, Black people's blood coagulates more quickly than whites’ and whites are less likely to have a stroke than blacks. The first is not true, while the second is. By the way there are differences, and these could be having an effect on the death rate of mothers. The participants then get a score based on how well they did and are put into two groups: those with low beliefs (-1 SD: below; did well on the quiz; fewer false beliefs) and those with high beliefs (+1 SD: did poorly on the quiz; more false beliefs). Note that, assuming normality on the quiz, these groups each contain about 15% of participants. Then, they asked the people who took part questions about pain and how to treat it. The key results are in Figure 4.

In Figure 4, both groups rate Black pain about the same; what changes is how each group rates White pain. It looks like this means that 15% of the medical students and residents are wrong and the other 15% are right. This seems to have less to do with racism and more to do with how people are trained in general. Figure 4's Graph B shows that the low belief group did better with Black patients, but it was close. This seems encouraging; on the other hand, the high belief group did worse in the other direction. Overall, this seems to imply that 15% did better with Black patients, 70% did about the same with both Black and white patients, and 15% did worse with Black patients. There is room for improvement, but this doesn’t seem to be a devastating statement of medical racism. Someone please correct me if I’ve interpreted this study incorrectly.

Another passage:

The CDC noted in a review of maternal mortalities in the US from 2017 to 2019, that 84% of the recorded maternal deaths were preventable.

Here is how the CDC defines preventable:

Preventability: A death is considered preventable if the committee determines that there was at least some chance of the death being averted by one or more reasonable changes to patient, community, provider, facility, and/or systems factors.

Note that the definition of "preventable" covers both patients and the community. This isn’t all on the medical community, and the report doesn’t give us a breakdown of which factor might impact which group. We don't know what percentage of maternal mortality in Black, White, or Hispanic women is thought to be avoidable.

One last thing to say about the last paragraph:

“We want people to have a transcendent, joyful, beautiful, sacred and health transformative birth. That’s what people deserve. They deserve to not worry about their safety leading up to their birth, they need to not feel like something is going to happen or be afraid or terrified to have a child or get pregnant.”

A perfect sentiment. The CDC report does include a breakdown of the underlying causes of death by race. To maximize results, one might look for outlier categories. One exists. 35% of White deaths, or 159 women, are caused by problems with mental health. Ome could argue that this is a "critical emergency." This is half of the deaths of Black women. For Hispanics, the maximum is also 24.1% of people with mental health problems and 34 deaths. This is certainly not a joyful experience. The same category has only 7% and 21 deaths for Blacks. In fact, no single category for Blacks has more than 16%, which is equal to 48 deaths. This shows that there are a lot of things to work on in order to lower Black maternal mortality. Hemorrhage is the worst group for Asians, with 31.3%, but only 10 people die from it.

Instead of focusing on race, The Guardian could have written a more fair and honest piece about maternal morality. Yes, Black mothers die at a higher rate than white mothers, but so much else is wrong in the U.S. that a better piece could have been written. At the same time, there is proof that the racism explanation doesn't hold up, which means that focusing on it takes time away from what's really going on. Let’s try working together to figure this out instead of dividing groups.

Please Share

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends) and by sharing this post on social media. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Data

OECD Maternal Mortality https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30116