Peak oil and U.S. oil production

Was Hubert correct, and what is the future for U.S. oil?

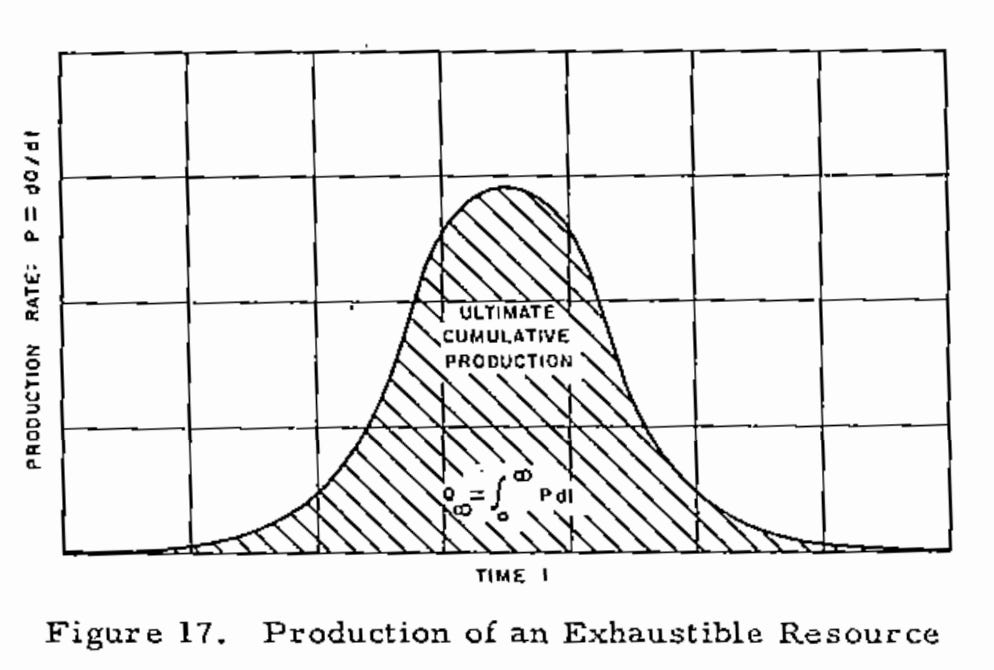

In 1962, M. King Hubbert authored the report Energy Resources: A Report to the Committee on Natural Resources of the National Academy of Sciences—National Research Council. In this report, he modeled oil production as a normal curve (Figure 1), where the area underneath the curve represented the total recovered oil.

In the same report, he went on to model U.S. oil production as well as other resources and predicted that the maximum amount of U.S. oil production, the peak, would occur around 1970 (Figure 2). Was Hubbert correct?

If we look at U.S. oil production in Figure 3, we would say that Hubbert was wrong and that the idea of peak oil has been debunked. Up until the late 1970s, Hubbert’s prediction was looking good, and then oil production saw an increase.

When we ask whether Hubbert was correct, we must analyze the assumptions he made. The first was that Alaska was not an oil-producing state at the time; therefore, he did not expect oil from Alaska. In fact, the first oil production in Alaska began in 1977. This explains the second peak in the mid-1980s.

So far, Hubbert is not too far off, but what occurred in 2010? U.S. oil output skyrocketed, surpassing the 1970 record in 2020. One of the data rules is that large disparities warrant skepticism. The surge that began in 2010 requires a deeper look.

Tight or shale oil was not in Hubbert's forecast, thus Figure 4 excludes tight oil production from total US production.

Hubbert now appears to be closer. If we exclude tight oil from traditional crude oil output, the U.S. peaked around 1970, and the graph is essentially bell-shaped except for the flattening over the last 15 years. Tight oil is more expensive to extract; thus, if we are extracting tight oil, there is no reason to expect traditional oil production to expand significantly. Sure, new technology may help us to extract more from wells, allowing us to maintain output for a while, but we can expect traditional production to continue its downward trajectory in the near future.

Tight oil by play

The question now is, how much tight oil do we have and how long can we keep producing it? I won't forecast the future, but we can look at the data on tight oil output in the United States by play (location) and draw some conclusions.

When we look at Figure 5, a few things stand out. All three plays in blue at the bottom are from the Permian. In other words, one play has produced more than half of all tight oil, and growth has slowed or ceased in recent years. If we add the purples to the blues, we can see that Texas accounts for over 3/4 of the tight oil, and there has been a plateau in recent years. Furthermore, despite a healthy economy, tight oil output has just recently exceeded its peak just before COVID.

None of this implies that tight oil production has reached its limit, but it does raise the question of how much tight oil is accessible and how long it will be until US oil production begins to drop again.

Tight oil is extracted from impermeable shale and limestone rock formations. It is more difficult and expensive to remove. Think of it as a step down from traditional oil. I don’t think there is another level down that is waiting for us to extract given the right technology and price point for oil. The fact is that oil is a finite resource that will eventually run out.

Moving away from oil is not a bad idea. At the same time, I still believe we will extract whatever we can. One possible benefit of global warming is that it may force us to do something we would otherwise have needed to do. We just aren’t going to move fast enough to stop much warming, but we may move fast enough to have a replacement as oil runs low.

Oh, and Hubbert, based on his assumptions, produced some plausible forecasts in 1962. One takeaway here is that you should judge predictions based on assumptions rather than just the outcome. Hubbert was largely correct in his modeling of conventional oil output in the lower 48.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.