QTRS Dec 12, 2025

Graphs, commentary, and interesting content for the curious

Holiday request: It would certainly be nice to add a few paid subscribers this holiday season, but if that isn’t in your budget or interest, then please help spread the word about Briefed by Data. Sharing posts and encouraging friends to subscribe and repost on the Substack app or in notes makes a real difference. 100 new free paid subscribers is the goal from now until the end of December. I thank you in advance.

Note: No QTRS next Thursday.

As I see it…

Hollis Robins of Anecdotal Value provides a strong critique of higher education in the essay Teaching Quality—Higher Ed’s Dirtiest Secret (12/11/2025). The claim, which I’ll generally agree with, is this:

Here’s what I see from my own experience: except at a small minority of expensive schools and some of the best flagships, only 25% of teaching at universities might be considered upwards of “good.” These are the talented, heroic faculty members devoted to their craft under grim conditions. But even talented teachers can only do a fair job delivering a quality education under conditions where the “student experience” comes first, where administrators enroll unqualified students and demand they be given a diploma in four years whether they learned anything or not. At many institutions, including community colleges, more than 50% of teaching is poor or, in the case of online asynchronous courses, nonexistent. Sub-par teaching was a crisis before the AI era; it is even more of a crisis now.

She also makes another important observation, which is as follows:

I also challenge anyone to show me any college or university marketing materials that guarantee the quality of classes students will take. You won’t find much. It’s impossible to guarantee quality because there is no operational definition of quality teaching. You may find guarantees of a “quality education” defined by small classes and award-winning professors with Ivy League PhDs, but you will not find an institution that guarantees that some percentage of the courses a student will take will be high quality.

The bottom line is that in higher education, there is zero accountability. To obtain tenure, you typically need a few published papers and positive student evaluations, but for teaching-focused colleges, this often means just publishing a couple over a six-year period. You must also join some committees, but that may only mean attending a few meetings a semester. It really isn’t that hard, except at elite colleges where the expectations for publishing are significantly higher. Once you have tenure, you can get away with doing much less.

Nowhere along the way do you need to demonstrate learning in your classrooms. No one even looks at how often you collect and assess student work or how long it takes to return it to students. I’m confident in saying that the less students have to do, the less they learn.

On top of all that, faculty are in a unique position in that they largely assign themselves most of their workload. Every time we give a test or assign graded homework, we have work to do. Giving just a midterm and final exam is much easier than, say, three class exams and a cumulative final. Assigning graded homework once a week or less is less work than multiple times a week.

As I see it, the lack of accountability and interest in trying to assess student learning is part of society's loss of confidence in higher education. In the past students accepted to college were brighter and better educated to begin with (see When grades stop meaning anything, 11/18/2025). How much they learned over four years mattered little. Except for a few selective institutions, students are now accepted into colleges that would have previously rejected them. They are less prepared and not as bright on average. They must acquire a substantial amount of knowledge in college to derive meaningful value from the experience. What happens when they don’t learn much and have large amounts of debt?

They can’t get a job they think they should to be able to pay off their loans. At the same time, they know that many of their classes, as they would put it, were BS. What advice will they offer someone considering going to college? What is their general opinion of college? It is a waste of time and money.

Similarly, people that hire these students without the skills and knowledge they would expect from a college graduate will end up with the same opinion. Once we reach a critical mass of these individuals, the narrative about the value of higher education shifts in the direction we are currently witnessing.

The bottom line is that if learning isn’t central to college, then what exactly is the value? Previously, the value of higher education was largely determined by the ability to gain admission to college, but that is no longer the case. On some levels, colleges are putting themselves out of business with no accountability for learning in the classroom.

Let’s go to some data.

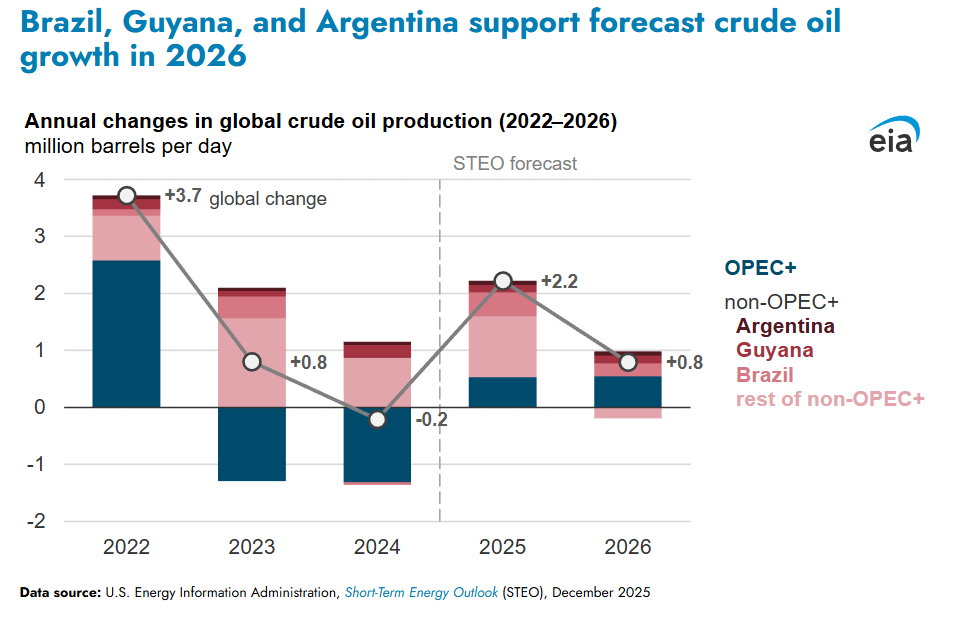

More oil

Here is the EIA’s estimate of 2025 oil production (12/17/2025) and prediction for 2026. Oil is too valuable for the world to stop extracting it.

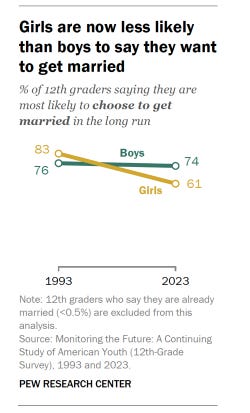

Who wants to get married?

The chart from Pew’s 12th grade girls are less likely than boys to say they want to get married someday (11/14/2025) is fascinating. Over a 30-year period, that is a large decline in girls' views on marriage.

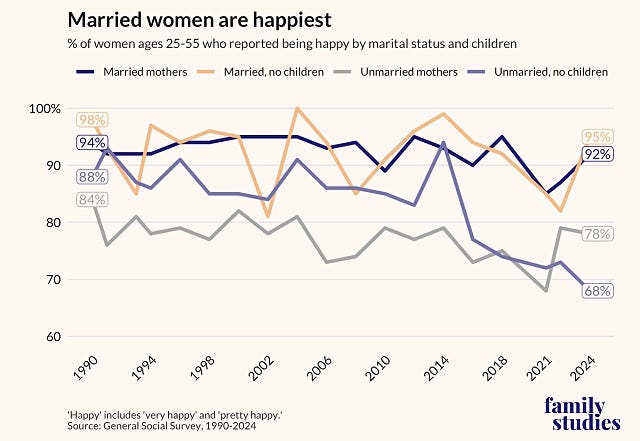

Meanwhile, the IFS has this graph from their article Sorry, Liz Gilbert, Married Women Are (Increasingly) Happiest of All (12/9/2025) with this key paragraph:

The repeated salvos against marriage and motherhood from left-leaning women help explain why so many single women, especially young and liberal ones, believe that marriage is a bad deal for them and a good deal for men. New research shows a “massive gender divide” in public views about the benefits of marriage, according to Dan Cox, a pollster at the American Enterprise Institute.

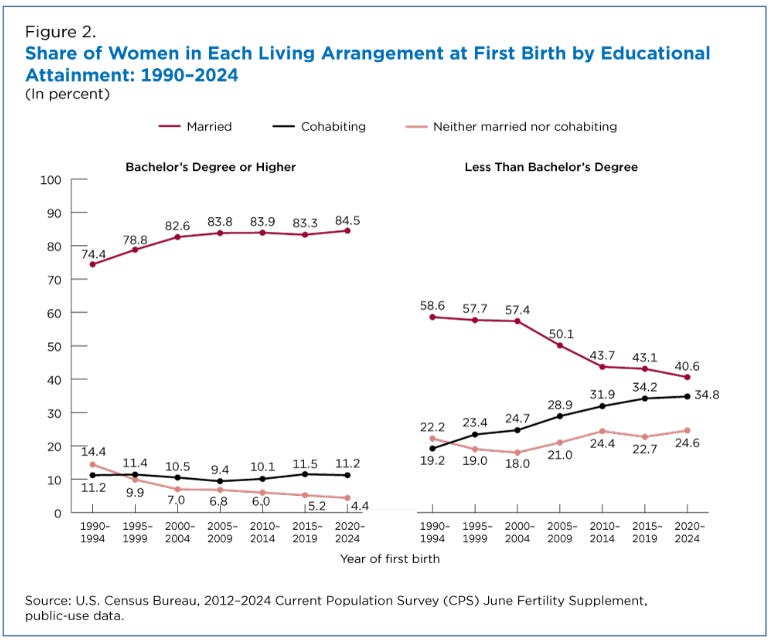

Now, left-leaning women are predominately college educated, making this graph from the Census Bureau fascinating. (12/16/2025) For women with a college degree that have kids, 85% are married. It appears there is a disconnect here. It would be nice if this graph was by liberal or conservative women, but it suggests that the attitude of college women that marriage is bad for them changes if they want kids, as they sure seem to prefer being married when having children.

Sampling matters

Introductory statistics courses tend to focus on performing statistical tests. There is little discussion on sampling, yet getting appropriate samples to make proper inferences is hard and critically important. Here is a good example stated in the title of the NBER paper Trials Avoid High-Risk Patients and Underestimate Drug Harms. Here is the abstract if you want more.

The FDA does not formally regulate representativeness, but if trials under-enroll vulnerable patients, the resulting evidence may understate harm from drugs. We study the relationship between trial participation and the risk of drug-induced adverse events for cancer medications using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program linked to Medicare claims. Initiating treatment with a cancer drug increases the risk of hospitalization due to serious adverse events (SAE) by 2 percentage points per month (a 250% increase). Heterogeneity in SAE treatment effects can be predicted by patient’s comorbidities, frailty, and demographic characteristics. Patients at the 90th percentile of the risk distribution experience a 2.5 times greater increase in SAEs after treatment initiation compared to patients at the 10th percentile of the risk distribution yet are 4 times less likely to enroll in trials. The predicted SAE treatment effects for the drug’s target population are 15% larger than the predicted SAE treatment effects for trial enrollees, corresponding to 1 additional induced SAE hospitalization for every 25 patients per year of treatment. We formalize conditions under which regulating representativeness of SAE risk will lead to more externally valid trials, and we discuss how our results could inform regulatory requirements.

The spinning CD

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you think I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I would rather know the truth and understand the world than simply be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. I encourage you to share article ideas, feedback, or any other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College, holding a PhD in math (stochastic processes), an MS in applied statistics, an MS in math, a BS in math, and a BS in exercise science. I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I am a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations, and I’m open to job offers (a full vita is available on my faculty page).

That NBER paper on trial representativness is a perfect example of selection bias in action. I've seen similar issus in other fields where the sample population doesn't match the real-world target. The 15% difference in predicted SAE rates between trial enrollees and the actual target population is massive when scaled across millions of patietns.

I’m being treated for Stage IV lung cancer by one of the newer immunotherapy treatments. I presume the voluminous lists of possible side effects that accompany advertising for the drug are compiled from reports gathered during clinical trials. People who have cancer, especially those in advanced stages, have symptoms…regardless of whether they are being treated with useful drugs or placebos. It seems to me that the decision to include or exclude a given patient in the clinical trial has a very substantial effect on the overall results of the trial. I’ve often wondered how they determine if a symptom was caused by progression of the underlying disease or by the treatment.

Interesting stuff today. Do you think the tide is beginning to turn with respect to expectations for America’s universities? I fear it is wishful thinking.