Today's post will be a little different: less data and a little more free thought. I'm putting out a few ideas that aren't completely formed. You can call it a rant if you want. Leave a comment to let me know what you think and, more importantly, what I got wrong or missed.

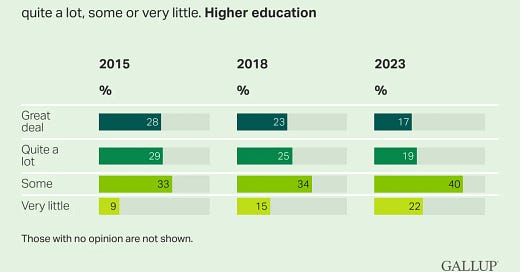

In a previous Quick Takes post with Figure 1, I noticed that confidence in higher education has fallen. To explain part of this decline, I'd like to provide three themes that I consider self-inflicted wounds. When I say higher education, I really mean a regular college, not the Ivy League or other privileged institutions.

Here are three themes I will discuss at varying lengths:

Amenities and the “Experience”

Return on Investment

Assessment

Amenities and the “Experience”

In order to compete for students, institutions offered numerous perks and focused on the college experience. There are articles about colleges with the best pools. Is Figure 2 an image of a vacation spot or a college? It's from Iowa State University.

Such amenities do not help learning but instead add costs. More crucially, they begin to shift a college's emphasis away from education and toward the experience of being a student, while also alienating professors. This appears to be an obvious blunder. When college marketing resembles a resort vacation, you are undervaluing your main product, education. These perks aren't free, and when higher education expenses rose, partly due to the perks but also for a variety of other reasons, universities were forced to explain the costs. This brings us to the topic of return on investment.

Return on investment

The return on investment is a typical argument used to justify the expense of college, which means that college students generally make more money, hence the cost of college pays off. This appears to be a wise decision at first, but it is ultimately a mistake. The data used to show that college graduates earn more money is not drawn from a random sample. A college student, for example, is more likely to be motivated, have a higher IQ, and/or come from a more supportive family-related situation. For instance, see the article The College Completion Gap and How to Bridge It. It shows (Figure 3) that students from married families are more successful, although this is more likely attributable to financial stability and resources than anything else.

Who's to say these students wouldn't be okay financially if they didn't go to college? In fact, some students and parents are concluding that they may not need college or may not see a return on investment. Hey, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg never finished college, which isn't a reason not to go to college, but it's a convenient one.

But something else happened with the return on investment argument. With this reasoning, colleges themselves were focusing students on the job they would earn to cover the expense. In other words, you attend college to get a job; therefore, everything you learn in class should be relevant to your future career. A career-focused major has nothing wrong with it, yet students should be getting more out of college than specific job skills. More crucially, the narrative of developing intellectual skills and habits in college is being lost. This is referred to as higher education capital in the book The Real World of College, but I prefer intellectual skills and habits.

Do you attend a college calculus class, for example, to be able to take a derivative later in life or to improve your ability to employ abstract notation and analyze graphs and functions that reflect real-world ideas? Is it better to take a programming class solely to learn how to write code or to increase one's ability to think linearly? Is it more important to read Shakespeare to say you've read Shakespeare or to develop your capacity to interpret rich, sophisticated language? I would argue that the second component, skills, is just as vital, if not more so. Even courses that appear to be vocational in nature, such as accounting, require significant intellectual skill development. Problem solving, critical thinking, and adaptability are frequently listed as desirable talents by employers. These abilities stem from the larger intellectual abilities that college courses should build. The true benefit of education is the development of intellectual skills and habits, but due to the emphasis on job skills and experiences, colleges have undervalued their main product.

Another issue with the return on investment argument is what happens when the cost of college rises and future employment does not pay off the investment. As institutions compete for students, they accept students who might not yield a good return on investment. Worse, the goal of retaining students to maintain revenue could be at odds with the return on investment argument. Is college meaningless if there is no apparent return on investment? No, because the intellectual skills and habits cultivated have value outside of the work market.

Assessment

Assessment and student learning outcomes have been placed on college campuses by accrediting bodies. This appears to be an excellent idea at first glance; however, there are two major problems. First, good assessment is expensive, and colleges did not and still do not invest in it. This is articulated well in the article Toward an Improvement Paradigm for Academic Quality (page 14 in Liberal Education Winter 2017).

The problem is that assessment data can be either cheap or good, but are rarely both. The fact is that good evidence about student learning is costly.

Higher education has spent money that achieves little to improve education while pleasing accrediting organizations. Second, and related to the preceding point, poor assessment has shifted the emphasis to content, such as the ability to take a derivative, rather than broader skills, such as the ability to use abstract notation and interpret graphs and functions that describe real-world ideas, primarily because the former is easier and less expensive to assess.

Conclusion

In the end, I believe that the narrative that higher education should be improving intellectual skills and habits, often known as higher education capital, has been lost. The higher education system needs to take a good, hard look in the mirror and acknowledge that it is at least somewhat to blame for the societal loss of confidence.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.

I wonder if a fourth factor is more hidden: the high number of students who go to college but don’t graduate. In a large national study, Clark and Allensworth study HS GPA and ACT/SAT scores as a predictor of college graduation. For example, students with a 3.0 to 3.25 HS GPA only graduate in 6 years about half the time in average. Think about the huge number of students who go to college, pay (or borrow) a ton of money, and leave without much to show for it. I imagine this group has lost a lot of faith and confidence in higher ed. Does most of the ROI data about the value of college only study people who actually graduated?

So many possible variables to consider...! (The fun stuff, truly, is thinking about all the possible explanations.) Type of college, non-profit or for-profit; 2-year or 4-year. Age at enrollment or re-enrollment – 18? 23? etc. Type of college – residential, dormitory, traditional age students, OR commuter, mixed-age, etc. How much debt is incurred and what sorts (parent-cosigned loans? loans via federal gov't?) What is a person told or led to believe about 'college' and it as an investment or a goal? Is there a perception that 'college' alone 'should' bring heaps of job offers and life satisfaction? I could go on and on from my sociological perspective....