With the destruction caused by the LA wildfires, there have already been a few articles about insurance. Here are a few key quotes from three such articles.

The NYT California’s Insurance System Faces Crucial Test as Losses Mount (1/14/2025) has this to say:

As of last Friday, the FAIR Plan had just $377 million available to pay claims, according to the office of Senator Alex Padilla, Democrat of California. It’s not yet known how much in claims the plan will face but the total insured losses from the fires so far has been estimated at as much as $30 billion. Because the fires are still burning, that number could grow.

The California FAIR Plan is a program “created by state lawmakers in 1968 to cover people who couldn’t get standard home insurance for various reasons,” including homes “deemed too dangerous by major insurers” to insure. Further FAIR has to get lawmaker approval to increase rates. Needless to say, FAIR may have a financial problem.

From the Washington Post An insurance crisis was already brewing in L.A. Then the fires hit (1/9/2025), we learn

“We’re marching toward a future where insurance is not going to be available or affordable,” said Dave Jones, who served as California’s insurance commissioner from 2011 to 2018 and now directs the Climate Risk Initiative at the University of California at Berkeley’s School of Law.

One more from the Washington Post: California isn’t the only place where insurers are dropping homeowners (1/18/2025).

Insurers also have struggled to accurately price in the risk of promising to rebuild homes in the many parts of the country vulnerable to wildfires, hurricanes and wind storms. The computer models used to identify the riskiest areas, built on historical weather patterns, have been upended by climate change. Porter said he’s heard of hail models that are largely outdated because today’s storms can be so much bigger than in the past.

“I think we’re getting to a point where insurance could be unaffordable in some places,” Porter said.

None of these articles explain key facts about insurance. The first is that insurance hasn’t been making money on underwriting. The second is that insuring for events such as floods and wildfires, as opposed to cars, is a challenge.

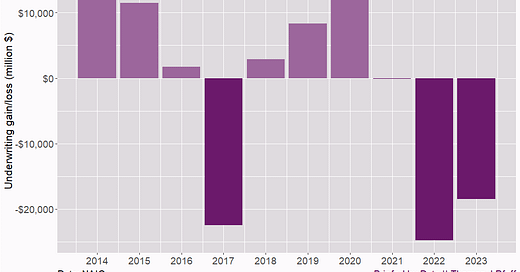

Underwritting The underwriting part of the insurance industry is the part where they collect revenue on policies and have costs associated with payouts on policies as well as paying staff, etc. Figure 1 is from the 2023 Full Year Results from NAIC (National Association of Insurance Commissioners). As you can see, the underwriting segment of property and casualty insurance experienced a loss from 2021 to 2023 and has been operating at a deficit for the past ten years. How do they make money?

The insurance industry makes money off investments. Premimums are paid up front, and profits from previous years are invested, and that is where insurance is making money. Figure 2 has the data.

We don’t need to feel bad for the insurance industry, as they are making money, but exactly in the way we think. The fact that the underwriting part of companies is losing money suggests that premiums are priced competitively. The fact that investments are making all the money suggests that a state can’t enter the insurance marketplace, such as California’s FAIR, so easily as they wouldn’t have the historical investment income to work with and would have to price premiums much higher. Again, I’m not worried about the insurance industry’s profits, but I think this information about their business is interesting and helps us understand why they won’t insure for some events such as wildfires, hurricanes, and floods.

Independent events Before climate change and increasing extreme events, as well as more homes in risky areas, insuring for events such as wildfires, hurricanes, and floods was already tricky. Let me start with a basic example with car insurance.

Assume we have 100,000 cars to insure. Each care has a 1/500 chance of an accident, and if one occurs, the average cost of repair is $2000. How much do we charge each car owner? Each car’s chance of getting into an accident is independent of all other cars, like rolling a 500-sided die with 1 representing an accident. In this case, we simply multiply 100,000 * 1/500 = 200 to get the expected number of accidents. Our total outlay will be $2000 * 200 = 400,000. Divide that by 100,000 to get a base fee of $4 for each car owner. We’ll have to add to that a fee to cover operating expenses, a reasonable profit, and something to cover variation, as we expect 200 accidents, but it could be more or less. The more cars we insure, the more likely we are to be close to the expected number of accidents (Law of Large Numbers and why casinos always make money). None of this is gambling; it is all very predictable. In the real world, the modeling is more sophisticated to assess the likelyhood a person will get into an accident (charge teen males more for this) and the cost of repairs (a Civic is cheaper to fix than any BMW). You get the idea.

Currently, there are over 10,000 homes destroyed in the LA fire. The problem with wildfires, floods, hurricanes, etc. is that each house isn’t independent of nearby homes in the chance of being effected. In other words, an insurance company has to be able to pay out for a large number of claims all at once.

In the car example, it would be as if there was a chance of say 10,000 cars getting into a big pile up. This would cost the insurance company 10,000 * $2,000 = $20,000,000 if it happens. Even if the chance is small, this is now effectively gambling. It can’t be controlled by playing averages. You have to charge very large premiums to gather the cash to cover the event if it happens sooner than later, and if it happens too soon, you’d start cancelling policies or jacking up rates.

In the case of climate change, the chances of such events have increased. At the same time, we have more homes that are more expensive in high-risk areas, meaning the payout would be higher. Remember, insurers are already losing money on underwriting, so it makes sense to exit the natural disaster insurance market.

Now, when states start entering the insurance market, that really means the taxpayers are going to cover disasters. If insurance companies see this as a loss, taxpayers may not want to cover them either. This is the conversation that needs to happen. For example, if someone wants to build in a known flood plain that no insurance company will insure, should the government do this or should society say go head, but if your house is flooded, we aren’t paying for it? What about hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes? The answer may not be the same for each. Leave your thoughts in the comments.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. We should all be forced to express our opinions and change our minds, but we should also know how to respectfully disagree and move on. Send me article ideas, feedback, or other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD Math: Stochastic Processes, MS Applied Statistics, MS Math, BS Math, BS Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations.

Did taxpayers say “let’s enter the insurance business in markets that insurers predict large losses.” I don’t think so.

Let wealthy people who can pay cash go ahead and rebuild without insurance. Many will.

The same should apply to beachfront homes in hurricane-prone areas.

The higher insurance rates should have been the market signal to stop building in disaster prone areas. Now either the taxpayer are going to have to foot the bill or the government will have to start regulating where you can and can't build.