The title of the Inside Higher Education article, Faculty Gender Pay Disparities Persist, Even at Vassar with subtitle Men have historically made more than women in academe—and for full professors, the gap has widened in recent years, making it clear that they have the viewpoint that the pay difference is wrong and likely due to sexism. A group of women full professors at Vassar have filed a federal lawsuit as a result of this disparity. Because the report just gives superficial facts, let's take a look at some of their claims and offer some possible reasons. We'll start with Data Rule 1: Don't make assumptions based on a single factor. (I’ve decided to start naming rules.)

The American Association of University Professors, analyzing data from more than 375,000 full-time faculty members across 900 institutions, said men averaged more than $117,000 in annual salary, $20,800 more than women. Excluding assistant and associate professors and only looking at full-time, full professors, men averaged $156,700, $20,300 more than women—and 65 percent of people at this higher-compensated rank were men.

The quote's link will lead you to an AAUP data dashboard with salaries for men and women based on rank (assistant professor, associate professor, etc.) from 2016 through 2022. A difference of $20,300 is significant. Men earn 15% more than women in the same position. Before we go to Data Rule 1, we must first apply Data Rule 2: Large disparities warrant skepticism. The notion that colleges are so sexist that men are paid 15% more than women should be questioned. It may or may not be true, but it should not be taken at face value. Returning to Data Rule 1 The AAUP data lacks two critical variables: age and discipline.

Age and years of employment

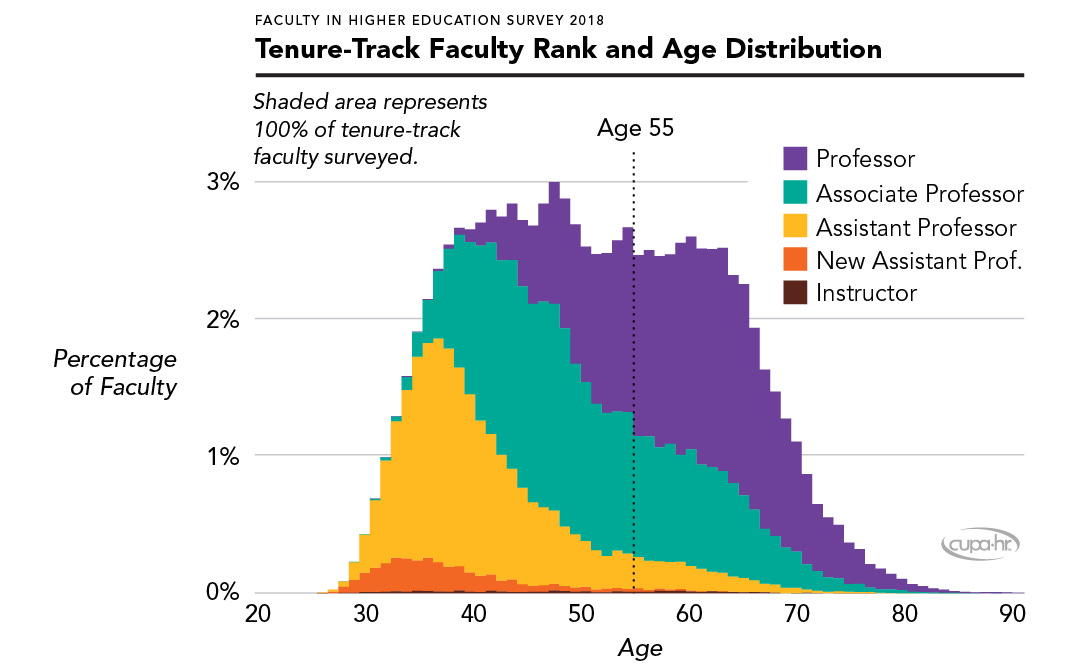

It is possible that the typical male full professor is ten years older than the average female full professor. That equates to ten years of raises, and with a salary of more than $100,000 and only 2% annual raises, the $20,300 is explained. Even if males were 5 years older and raises were slightly better, some or all of the disparities may be explained. I can’t find data about age and years in rank, but I might be able to infer it. Figure 1 is from a January 2020 College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR) paper using data from 2018.

Notice that in Figure 1, there is a group of professors aged 70 to 80. This means they were hired 40–50 years ago, at roughly the age of 30. Women had yet to become the majority in higher education 45 years ago, in 1978. A male full professor's average age is likely to be older than a female full professor's average age and to have worked at the college for a longer period of time. With this next paragraph, the writer attempts to imply that something suspicious is going on with full professor salaries:

The latest year from those Chronicle data, 2021–22, showed Vassar’s male full professors averaged $153,200 — $13,900, or 10 percent, above their female colleagues. The pay gap was as high as 14.6 percent in 2019–20, but it was only 7.6 percent about 20 years ago, according to data in the case.

A short Google search reveals that Vassar has 189 tenured faculty members. Full professors are probably fewer than one-third of the total, so let's assume 50. This is a tiny cohort, and the retirement of a couple of long-serving female full professors may raise the mean difference. Data Rule 3: Means from small samples can deceive. The bottom line is that we can't conclude that compensation disparities are a problem without knowing the ages of the full professors.

Discipline

What is the distribution of discipline by sex? We don’t know about Vassar, but here is the graph of the largest enrolled areas by sex, Figure 2, from my Female vs. Male Master’s Degree Enrollment article.

In general, computer science and engineering professors are compensated more since they can earn more money in industry. Simultaneously, health, psychology, public administration, and education are paid less. Based on this, the higher-paid faculty are almost certainly disproportionately men due to their field of study, resulting in a wage difference.

It is worthwhile to pause for a moment and explain why, for example, industry pays a computer scientist more than a health professional or educator. In one word: scalable. A brilliant app or technical gadget can be sold to millions of people, so it can be extremely profitable. On the other hand, any business that directly services individual people, such as health, psychology, or education, has a limit to the number of people it can serve. So far, these industries are not scalable and have strict profit limits. This is why education is so costly. When a college has a student-to-faculty ratio of 12 to 1, it means that 12 students must pay the salary of one faculty member without including endowment or other income for the college. We can't conclude that the compensation disparities are related to anything other than the disciplines in which the full professors teach without knowing their disciplines. But what about fair remuneration for fair work?

“substantially similar work”

This is where I think the lawsuit could get really interesting.

The case, filed in U.S. District Court in the Southern District of New York, seeks monetary damages, equal pay for female full professors performing “substantially similar work” to their male colleagues and an end to allegedly discriminatory promotion and evaluation practices.

For starters, one may argue that all faculty members do similar work. We are all educators and scholars. This implies that colleges should pay computer science professors the same as history professors. If colleges desire computer science professors, the only way this works is if the wage of the history faculty member is raised to the level of the computer science income. In fact, all faculty wages would have to be raised to match those of the most costly academics on campus, which might be computer science faculty. This would significantly increase the expense of attending college for students. The cost of college is already expensive, and this would make it worse.

The second issue with this "substantially similar work" is that it is extremely difficult to quantify. Yes, all faculty members teach, conduct research, and serve on committees. So far, it has been extremely difficult to quantify teaching excellence, yet we all have an idea of who the best and worst teachers are. Similarly, it is difficult to measure research. As other universities do, we can count the number of articles authored, the quality of publications, or the number of citations. This has drawbacks because it would encourage faculty to conduct specific research rather than contemplate longer-term goals that may or may not succeed. This would not be beneficial to society, in my opinion. Finally, there's service. I can confidently state that there are many faculty members who have been on numerous committees but have done little to nothing. Higher education operates on a lot of good will. It could get really interesting, and not necessarily in a good way, if we have to really start measuring who is doing more work than someone else.

Is the reverse okay?

The article has two paragraphs that don’t seem to concern them:

At one of the Seven Sisters, Barnard, female full professors made $11,200 more than male professors last fall.

When all Vassar professor ranks were taken into account last fall, men averaged only around $1,900 more than women. That gap has been closing since fall 2020. And, last fall, for the first time since fall 2017, Vassar’s female assistant professors averaged more than their male counterparts, to the tune of $1,500.

The male faculty members at Barnard, as well as the male assistant professors at Vassar, appear to have a lawsuit. So, did they pay women more knowingly? Perhaps there are other factors at work, such as when males are paid more. In any case, Inside Higher Education will write a separate essay explaining why this is okay.

The crucial idea here is that the media must cease making assumptions. Other explanations exist, and if they are right, Insider Higher Education will most likely not correct the record. I've simply offered plausible explanations, and it's possible that discrimination is taking place, though I doubt that it accounts for even a majority of the pay gap. In any event, the Vassar case will be worth following up on, and I will make every attempt to do so in order to set the record straight.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.