One of the long lists of things that aggravates me is the lazy comparison of the representation of race and ethnicity to the general population. One example of this is in Affirmative Action, SAT Scores, Asian Excellence and Harvard (7/5/2023). It makes no sense to compare the percentage of Asians at Harvard to the general population. Harvard doesn’t draw students from the general population. As I noted

Despite the fact that Asian students only make up about 6% of the college-age population and White students only make up about 53% of the college-age population, there are practically an equal number of them scoring in the 1400–1600 range.

Thus, one would expect Harvard to have more Asians than their overall population percentage. Please refer to the article for further details.

I was reading Can Universities Still Diversify Faculty Hiring Under Trump? (4/17/2025) in Inside Higher Education. This is standard fare for the publication. But here is the subheading:

The professoriate doesn’t demographically represent the U.S.—or the college student—population. The government’s anti-DEI crusade threatens efforts to address that.

The issue is that neither the general U.S. population nor college students make up the hiring pool for faculty. They largely hire from the Ph.D. pool. Here is a key paragraph (bold mine):

One example of the disparity: As of November 2023, only 8 percent of U.S. assistant professors were Black, according to the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources. That’s significantly less than Black representation in the U.S. population, currently estimated by the Census to be 13.7 percent. And the CUPA-HR data showed that the Black share of tenure-track and tenured professors decreases as rank increases—only 5 percent of associate professors and 3.6 percent of full professors were Black.

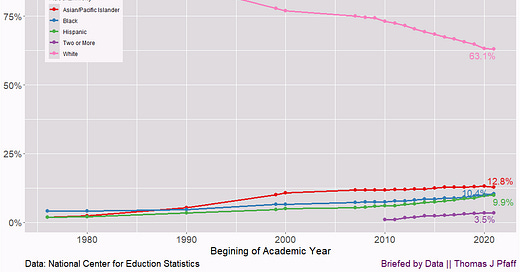

This is lazy and sloppy. Let’s take an honest look at the situation. Let’s go to the data, sourced from the National Center for Education Statistics, with 2022 as the most recent year available. We start with Figure 1.

Let’s pause for a moment and recall from the post The Race Ethnicity Confusion (9/24/2024) that those in their late 20s, a common age for earning a Ph.D., are 7% Asian, 14% Black, 23% Hispanic, 53% White, and 3% Two or More.

As we can see, the percentage of Ph.D.s earned by White people has fallen steadily since 1980. It is now at 63%, a 10% overrepresentation of the overall population. Asians earn 13% of the Ph.Ds while only being 7% of the overall population. For Blacks it is 10.4% compared to 14%, and 10.4% vs. 23% for Hispanics. If one wants to be concerned about underrepresentation here, it is with Hispanics, not Blacks, as they are getting close to their overall population percentage.

Asians, of course, are overrepresented but also stable for a couple of decades; Blacks are increasing, but slowly, while Hispanics seem to be on the move. It is fascinating to notice the rise of Asian Ph.D.s from 1990 to 2000 and how it corresponds to the decrease of White Ph.D.s. Ultimately, colleges hire faculty from this pool.

Before moving to Figure 2, we should note that faculty, once they have tenure, tend to stay in their jobs for decades. In other words, faculty representation is going to change very slowly.

Figure 2 provides faculty representation by race and rank. Instructors are not tenure-track and are often part-time faculty. Lecturers are similar but often more stable, as they are typically full-time teaching faculty at research universities. Assistant professors are recent hires, and it usually takes 7 years to become an associate professor. Promotion to professor status can take anywhere from an additional 7 years to an indefinite period. In general, professors have been at the college for 14+ years.

Let’s start with Asians. The Ph.D. percentages for all three tenure-track ranks reflect their proportionate representation. They have been stable in the Ph.D. production since 2000, and so this makes sense.

For the Black population, their percentage at the assistant professor rank of 7.2% is slightly below their 10.4% Ph.D. production. In 2016, the percentage was 8.8%, but hiring in higher education has since slowed down. The average of the last 6 years is 9.4%. Is the 7.2% low or just a little variation? Hard to say, but it isn’t off by much.

There is one more catch here, and that is the Ph.D. data includes U.S. citizens and non-citizens. It turns out that there are a fair number of Black Ph.D.s that are international. Consider this from The Number of African American Doctorates Reaches an All-Time High (2/14/2024) from the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education:

If we restrict the data to U.S. citizens and permanent residents of this country, we find that 2,647 African Americans earned doctorates from U.S. universities in 2022. This is the highest number ever recorded. African Americans earned 7.5 percent of all doctorates awarded to U.S. citizens or permanent residents of this country. This is just less than half the percentage that would exist if racial parity in doctoral awards was achieved.

Based on this, the percentage of Black assistant professors is relative to what it should be when we consider the hiring pool.

What about Hispanics? They represent only 5.8% of assistant professors with Ph.D.s, and over the last six years, they earned 8.85% of Ph.D.s. I’m not finding a similar breakdown of citizen vs. non-citizen Hispanic Ph.D.s, but Hispanics have more of a case for discrimination than Blacks, although I’m not saying they have a case. There are other issues here, such as the areas people choose for their Ph.D. and whether or not that matches the hiring needs of colleges.

At this point, the Inside Higher Education article is nonsense. There is little to no evidence of discrimination against Blacks in recent hiring. How might colleges address the situation if the pool of Ph.D. candidates does not reflect the overall population? If you want to argue for affirmative action, favoring one group, you are also favoring discrimination against another group. That doesn’t work out well for society.

Why does this matter? In my mind, the focus on hiring college faculty is misguided and lazy. The problem isn’t on the hiring side; the problem is on the production side of the Ph.D.s. Why aren’t there more Black Ph.D.s, although they are close to their population percentages? Furthermore, why is there a lack of Hispanic Ph.D.s, considering their representation is significantly below their population percentage? These are the hard questions that need to be answered, and then it must be decided if there is a problem, as you can't force people to do what they don't want. This is yet another challenging issue to tackle. This is why I say it’s lazy. Complaining that colleges aren’t hiring enough of one type of person when the pool is limited is just virtue signaling. Improving education outcomes starting in K-12 for the same group is really hard.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. We should all be forced to express our opinions and change our minds, but we should also know how to respectfully disagree and move on. Send me article ideas, feedback, or other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD Math: Stochastic Processes, MS Applied Statistics, MS Math, BS Math, BS Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations.