An recently published essay in Harvard Magazine, AWOL from Academics (March–April 2024), states some of the quiet things out loud, but it also overlooks a major point: higher education appears to be doing everything it can to put itself out of business, although the title suggests this. Let me clarify using quotes from the text. Please keep in mind that the comments I've made below do not apply to all students, professors, or colleges, but to a large enough group.

Hours studying

I was surprised to find I spend far, far less time on my classes than on my extracurricular activities—working as a research assistant, editing columns for the Crimson, or writing for Harvard Magazine. It turns out that I’m not alone in my meager coursework. Although the average college student spent around 25 hours a week studying in 1960, the average was closer to 15 hours in 2015.

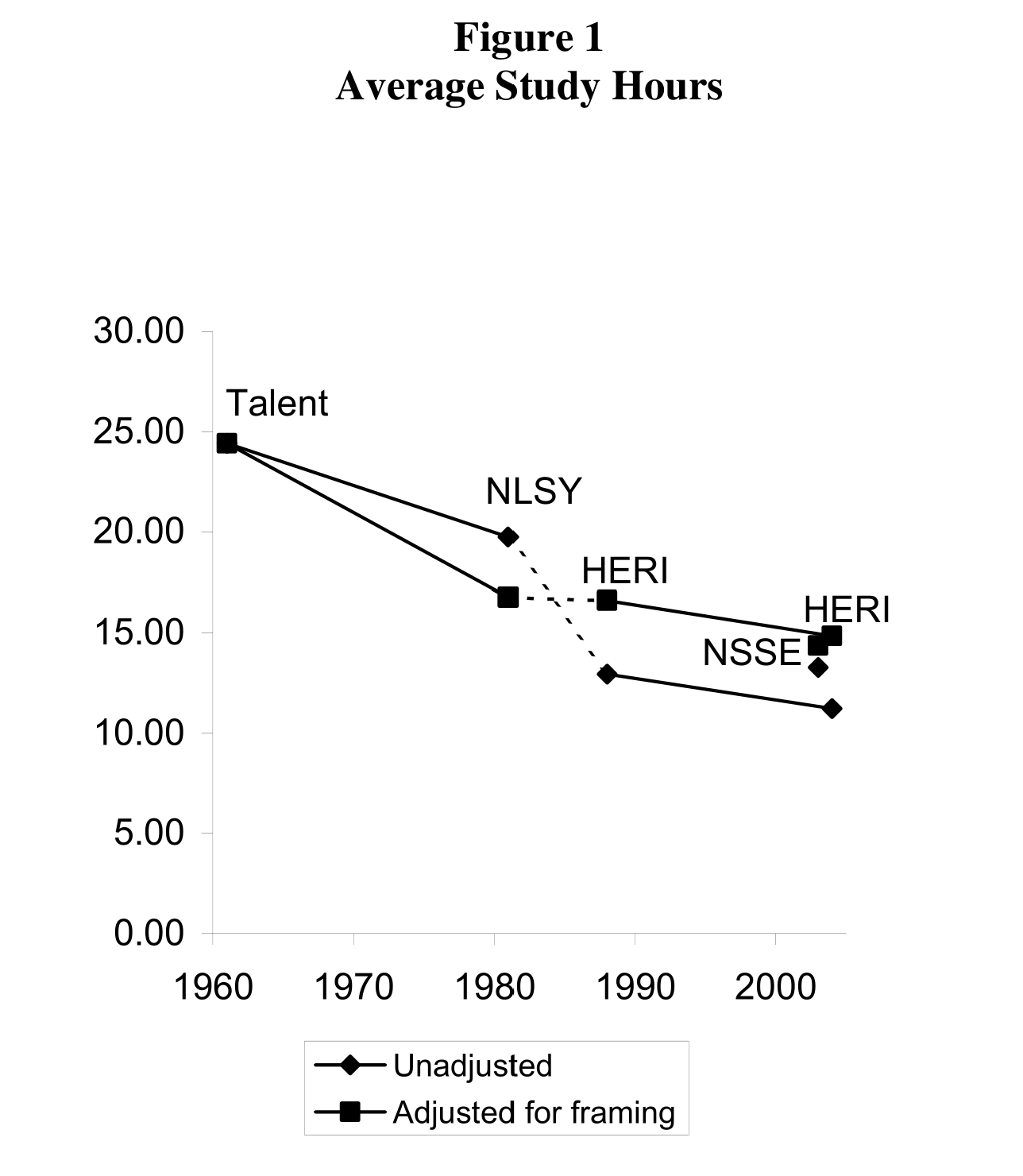

Apparently, you are not required to cite any sources for data in Harvard Magazine. The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE "nessie") is the place to start for information on how much time students spend studying. Figure 1 shows the data for 2023.

Every year, the NSSE conducts surveys of first-year students and seniors. As you can see, the two groups of students have relatively similar study times. In both cases, more than half spent 15 or fewer hours, with 70% spending 20 or fewer hours. The Carnegie unit, which most schools embrace, states that students should spend two hours outside of class for every hour spent in class. The normal load is 15 credit hours; therefore, students should put in approximately 30 hours outside of class. Approximately 10% of students report doing this, and most are doing less than half. Has this changed with time? NSSE does not have much historical data; therefore, I'll need to look elsewhere.

Figure 2 is from the 2010 publication The Falling Time Cost of College: Evidence from Half a Century of Time Use Data, published in the Review of Economics and Statistics. The paper compiled time-use statistics from multiple sources.

We do have a 20-year gap between Figures 2 and 1, but it appears that self-reported study time has been cut nearly in half. Worse, I would suggest that self-reported study hours in 2023 are actually lower than they were 20 years earlier due to screen distractions.

I'm going to make a bold statement: less time studying equals less learning. Maybe it's not a one-on-one relationship, but something less is happening, and at what point are students not learning enough to justify attending college? Perhaps we are cancelling some student loans because students didn't spend enough time learning in college to justify it.

Faculty members are mostly to blame for this situation. Faculty are in a unique position in that they generally allocate their own workload without supervision. If you wish to work less, give less homework that needs to be graded, as students tend to avoid homework that is not graded. Faculty provide fewer graded assignments, students do less, learn less, and college becomes less valuable. This is self-inflicted. Furthermore, students are receiving higher grades despite studying less.

Grade inflation

Rising grades permit mediocre work to be scored highly, and students have reacted by scaling back academic effort. I can’t count the number of times I’ve guiltily turned in work far below my best, betting that the assignment will nonetheless receive high marks.

Although a decade old, the best data I’ve found on grade inflation comes from GradeInflation.com. Figures 3 and 4 are a nice summary.

By 2013, private schools had an average GPA of around a B+. Meanwhile, the percentage of A grades had reached 45 percent. I believe this has gotten worse in the last decade. Again, this is self-inflicted. Faculty set the standards and assign grades.

The issue with higher education is that one of the values of a college degree is to communicate to society a person's intelligence, aptitude to study, and tenacity. What exactly is a 3.3 GPA signal today? If not much, what's the point? In other words, the transactional model of college may be in jeopardy.

This attitude is one manifestation of what Fischman and Gardner call a “transactional model” of college. According to their book, a so-called transactional student “goes to college and does what (and only what) is required to get a degree and then secure placement in graduate school and/or a job; college is viewed principally, perhaps entirely, as a springboard for future-oriented ambitions.” I’m ashamed to admit that this approach has all too often fit my own approach to school, and I can’t help but notice that it also describes many of those around me.

Extracurricular activities

Each week, on the days leading up to the seminar, I faced the difficult choice between doing the class’s readings or finishing extracurricular work. I invariably chose the latter, both because the cost of not doing the readings was low and because the benefits of doing other tasks were high. After all, I was relying on my research role for a reference and on my student newspaper articles as samples for an internship application.

One of the arguments mentioned in the Harvard Magazine article is that extracurricular activities are more valued. One of the issues here is that there aren't enough research positions or writers for the student newspaper to accommodate all students. This may explain why some students spend less time studying, but not the majority. Furthermore, if college is mostly or solely about extracurricular activities to complete a resume, people will eventually realize that they can gain this experience in much less expensive ways than attending college.

Critical thinking

Martin told me that he used to get more essays “where the student was trying to ‘jerk your chain,’ i.e., write something that completely contradicts what you’ve been teaching,” but this is no longer as common. That certainly resonates with my own experiences. When approaching essays, I often automatically start by thinking about what my professor or teaching assistant wants to hear, rather than what I want to argue or what I have authentically learned.

Instead of becoming wholly careless towards classes, then, students are often incredibly intentional about earning the (easy) A, at the cost of true or genuine curiosity. One of my classmates last semester, who is one of the more academically oriented people I know, told me that to get the best grade on an important essay, he simply “regurgitated the readings” without thinking critically about the material.

I think the quote here is more true than faculty want to acknowledge. If students are just regurgitating the readings, then they aren’t critically thinking. Of course, it is hard to do more than regurgitate (the classroom discussions?) when you aren’t doing the readings in the first place.

As time went on, the percentage of readings each of us did went from nearly 100 to nearly 0.

In the final class, each student was asked to cite their favorite readings, and the professor was surprised that so many chose readings from the first few units. That wasn’t because the students happened to be most interested in those classes’ material; rather, that was the brief period of the course when everyone actually did some of the readings.

On top of that, students can get away with missing a lot of class time with little to no penalty due to grade inflation. It is hard to argue that critical thinking happens when students don’t even attend class.

This fall, one of my friends did not attend a single lecture or class section until more than a month into the semester. Another spent 40 to 80 hours a week on her preprofessional club, leaving barely any time for school. A third launched a startup while enrolled, leaving studying by the wayside.

Colleges will argue that they are about teaching critical thinking. There is enough evidence in this essay to question how much of that is actually happening. I’ll add to this a quote from a previous Quick Takes:

It's not encouraging to read stories in the Chronicle of Higher Education (July 10, 2023) with this in the first paragraph:

He had on various occasions complained in faculty deliberations that the program with which he was associated had become too focused on “social justice” at the expense of its intellectual integrity. He was sanctioned for raising those concerns. A majority of the court disagreed that such speech is constitutionally protected.

The public good?

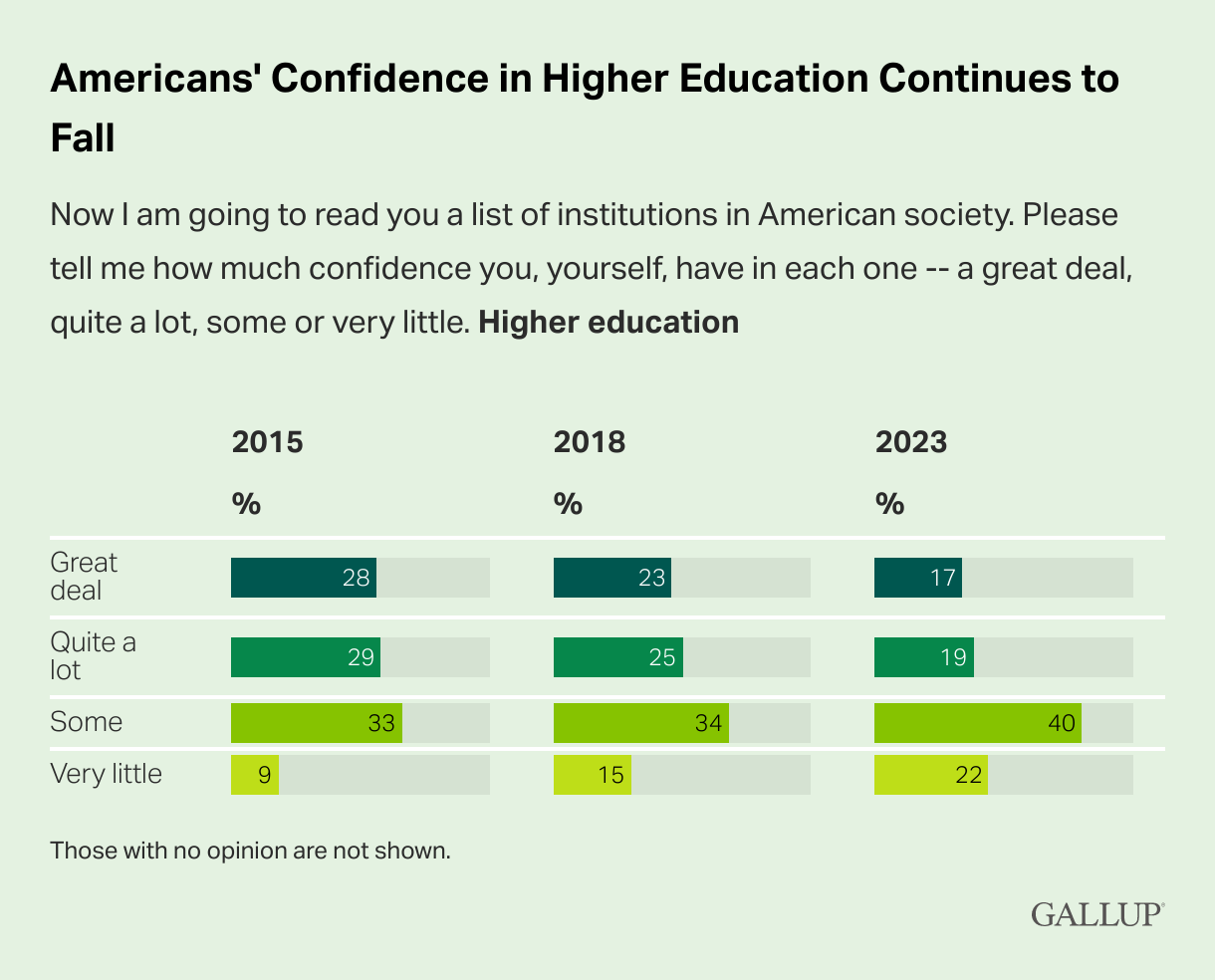

Colleges will argue that education the masses is beneficial for society. This assumes students are being educated. Full-time college is really part-time college. Students spend about 15 hours in class and another (unfocused?) 15 hours doing homework. For this, they have almost a 50% chance of getting an A in a course. They can skip a month of class without worrying and really aren’t being challenged to think critically. Is this chart from Gallup (Americans’ Confidence in Higher Education Down Sharply) really a surprise (originally used in this Quick Takes and also used in Some higher education missteps)?

Even worse, kids at "elite" colleges are graduating with minimal knowledge while on the path to becoming our future leaders. It appears that universities, like Harvard, are abdicating their responsibility by graduating the next generation of elites without having read much, learned much, gained any perspective, or developed much critical thinking.

The incentive structure

Let me conclude by highlighting the present problems and incentive systems in higher education. The basic purpose of any organization is to remain in business. There are fewer high school graduates, so institutions are urging kids to enroll. Many of these kids are unprepared for college success, and institutions must retain and graduate students in order to maintain a revenue stream. One approach to accomplishing this is to make college easier and more enjoyable. Figure 4 depicts the “Student as Consumer Era," where A grades rose rapidly with the goal of making students happy, which contrasts with demanding academics. Even worse, colleges like Harvard don't have these same pressures. They don't have enrollment challenges or funding concerns, yet they have devalued their own product. One might excuse or at least understand the choices of the average college that is trying to stay afloat, but what is the rationale for elite colleges?

In the end, both administrators and faculty are complicit. Both have devalued education, which is their product. At what point does the product become worthless, or at least not worth the money? I believe this is already starting to happen.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.

Oh this is straight to the point!! You make good points of course.... Hard to argue that faculty aren't responsible for some of these dynamics. If I were assigning a "term paper" and two exams, then indeed I would err on the side of grade inflation, because how could I assign Ds and Fs if I have offered students no opportunities to demonstrate learning, application, trial + error...? If I'm being told that I also have to balance students' mental health concerns within my course design, then yes, I will make it easier for them. If I am also told that every 10 students = $1,000,000 of revenue, then I'm implicitly being informed that I need to help retain students...and an easy class is part of that. Sigh.

I have indeed noticed that I get regurgitation as well as AI-bot-written answers, no matter how convoluted my prompts are. It means I leave the classroom wondering what the point is.