Note: If you like this article, please share it and subscribe.

The NYT posted an article yesterday titled I Study Climate Change. The Data Is Telling Us Something New with this first sentence:

Staggering. Unnerving. Mind-boggling. Absolutely gobsmackingly bananas.

I claim that nothing unexpected is happening, but this does not imply that there isn't a climate problem. In fact, later in the essay, it is noted that we are experiencing predicted warming, which again is bad but not surprising.

Does this acceleration mean that warming is happening faster than we thought or that it is too late to avoid the worst impacts? Not necessarily. Amazingly enough, this acceleration quite closely matches what climate models have projected for this period. In other words, scientists have long foreseen a possible acceleration of warming if our aerosol emissions declined while our greenhouse gas emissions did not. That’s what we’re now seeing.

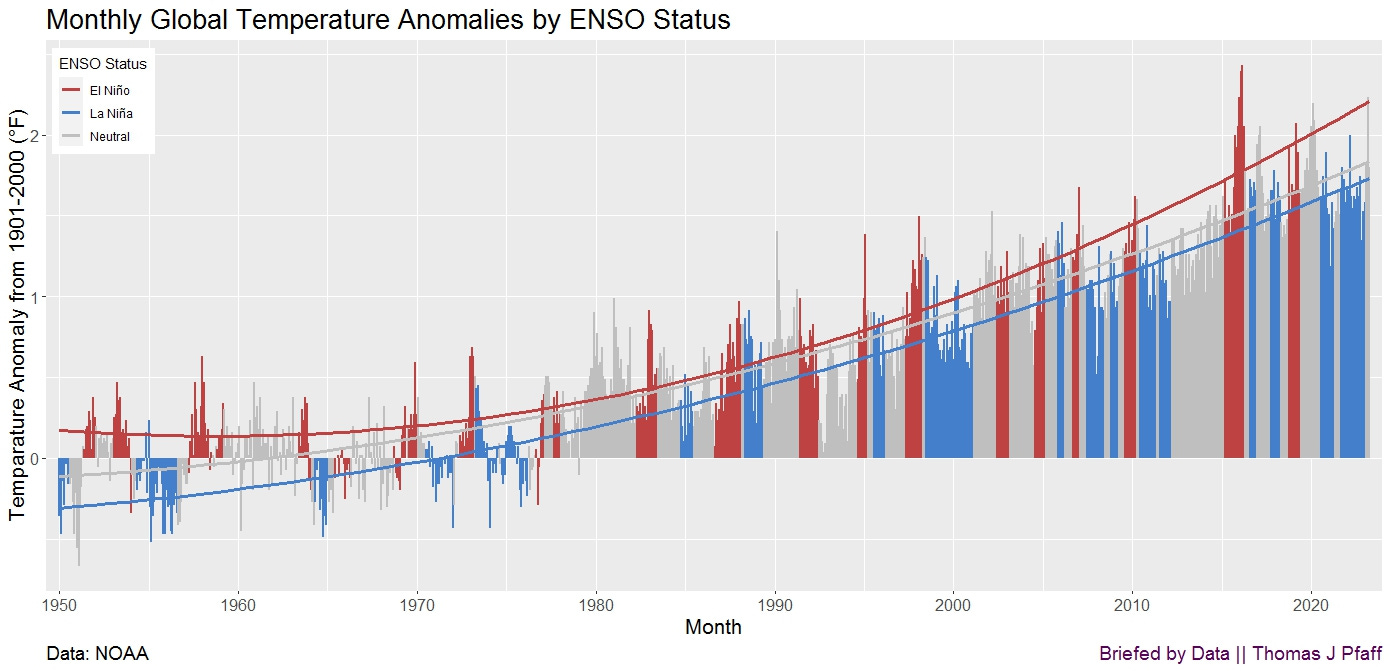

Before saying more about the article, I want to make a point with the animation in Figure 1, which illustrates a little calculus. Readers of Briefed by Data will recognize the graph in Figure 3. I first used it in the post The Three Trends of Climate Change. The Figure 3 graph tells us two important facts. First, climate change is not linear but has some curvature, which a quadratic can model well (I've been doing this for years; see my calculus projects page). This is where Figure 1 comes in.

A fundamental property of a quadratic function is that the slope of the curve increases. Figure 1 depicts this with a moving secant line spanning 20 years. The slopes of these secant lines are plotted in the inset graph. I used a quadratic function that, like climate change, increases by "4 degrees" over a "100-year" timeframe. As the secant line moves along the graph, the slopes of the secant line increase. Now, consider the following quote from the article:

And while many experts have been cautious about acknowledging it, there is increasing evidence that global warming has accelerated over the past 15 years rather than continued at a gradual, steady pace.

Given that global warming has seemed to be quadratic for years, the rate of warming will increase in the same way that the 20-year secant line slope increases, as seen in Figure 1. It's also worth noting that "a gradual, steady pace" indicates a linear rise, which has not been the behavior of climate change. I might dismiss all of this as me being overly mathematical, but then there's this graph, Figure 2 here, from the article.

Yes, as seen in Figure 1, the secant line will have steeper slopes in later years than in earlier years. Worse, they used lines of varying lengths, which leads to two issues. For starters, it prompts any alert reader to wonder about cherry-picking start and finish dates. Second, if the curve is quadratic, a longer secant line will have a lesser slope if they either stop at the same point or the longer (yellow in Figure 2) one ends before the shorter. Essentially, this graph demonstrates that the data does not grow linearly, which we already knew. There is no new information here. To be fair, the author may be attempting to indicate that a quadratic fit to data from, say, 15 or 20 years ago had less curvature than one today, but the work here does not prove that. In fact, why not just do that?

Now, let's look at my second issue, which also comes from Figure 3. I need to first note that Figure 3 uses anomalies relative to a 1901–2000 base period. I use it because NOAA does, although the top graph in the NYT story and the one in Figure 2 show anomalies in comparison to "preindustrial levels." It's unclear what time period they're using, and that’s sloppy, but it's probably earlier than in Figure 3, which will amplify the anomalies. This makes a comparison with the article impossible, but I believe I can still make my point. Answer the following question using Figure 3: How large of an anomaly do you expect when the next powerful El Niño arrives? Given that the large red bars in the graph are approximately a degree higher than previous high anomalies and that the trend has curvature, we might estimate 3 to 4 °F. In other words, something significant enough that a writer can write about as shocking or surprising but is actually easily predicted with a simple time series.

This is all really frustrating to me. What we're seeing isn't exactly “Staggering. Unnerving. Mind-boggling. Absolutely gobsmackingly bananas,” nor is the data “telling us something new.” Now, once this El Niño is through, I'll go over what happened and see whether the anomalies move into the 5+ °F zone, which indicates that something more than predicted occurred. Don't get me wrong: none of this is good news. I just don't think climate alarmist articles like these help. Worse, they almost always appear to end with unrealistic optimism.

On that front, there is some reason for cautious hope. The world is on the brink of a clean energy transition. The International Energy Agency recently estimated that a whopping $1.8 trillion will be invested in clean energy technologies like renewables, electric cars and heat pumps in 2023, up from roughly $300 billion a decade ago. Prices of solar, wind and batteries have plummeted over the past 15 years, and for much of the world, solar power is now the cheapest form of electricity. If we reduce emissions quickly, we can switch from a world in which warming is accelerating to one in which it’s slowing. Eventually, we can stop it entirely.

This is all true, but it is also true that offshore wind projects are having issues, there is a big inequality problem with CO2 emissions, renewable subsidies may be artificially lowering their price (even if I note in the post that the normalizing may be wrong), and minerals may be a problem. The conclusion:

We are far from on track to meet our climate goals, and much more work remains. But the positive steps we’ve made over the past decade should reinforce to us that progress is possible and despair is counterproductive. Despite the recent acceleration of warming, humans remain firmly in the driver’s seat, and the future of our climate is still up to us to decide.

So, “despair is counterproductive” at the end of an article that seems to be designed to scare us? Ok. In terms of the "recent acceleration of warming," I expect to be able to write the same piece in 5–10 years following another El Niño event.

My recommendation. We should continue to improve renewable energy production, but we shouldn't expect it to get us to net zero, at least not in time to prevent the major warming that is now unavoidable. Meanwhile, we should continue to invest in research and development for carbon capture, improved batteries, nuclear, and other methods of reducing CO2 and improving human lives. But we also need to invest in adaptation measures, and anyone who argues we should solely focus on CO2 reduction is essentially saying we should just let people die.

Please share and like

Please help me find readers by forwarding this article to your friends (and even those who aren't your friends), sharing this post on social media, and clicking like. If you're on Twitter, you can find me at BriefedByData. If you have any article ideas, feedback, or other views, please email me at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Thank you

In a crowded media market, it's hard to get people to read your work. I have a long way to go, and I want to say thank you to everyone who has helped me find and attract subscribers.

Disagreeing and using comments

I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than always be right. I'm not writing to upset or antagonize anyone on purpose, though I guess that could happen. I welcome dissent and disagreement in the comments. We all should be forced to articulate our viewpoints and change our minds when we need to, but we should also know that we can respectfully disagree and move on. So, if you think something said is wrong or misrepresented, then please share your viewpoint in the comments.