I find it common and frustrating that I often can’t get through the first paragraph or two of an article without questioning the accuracy of the text. This phenomenon occurred again when reading an article by The Climate Brink (can you guess their views of the world by the title?) entitled A worse-than-current-policy world? (4/7/2025). Most of the article is a discussion about the IPCC SSP (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways) version 3. It's interesting enough, but I'm not sure how literally one should take these scenarios, as I think they are meant more as guidelines. Besides, I’m still stuck on the first two paragraphs. The first:

The world has made real progress toward tacking climate change in recent years, with spending on clean energy technologies skyrocketing from hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars globally over the past decade, and global CO2 emissions plateauing.

Well, I think we have spent “billions to trillions of dollars” on clean energy technology, but spending money doesn’t mean it helped much. It was only two weeks ago that I wrote World energy production by source (4/1/2025) and said, “I know I keep saying this, but the fact is people want more energy, and renewables can’t even meet the increased demand, at least so far.” So far at least, the money spent hasn’t helped much, and one might question if we are getting our money’s worth.

It was the last few words that really got my attention. Is it accurate to say that global CO₂ emissions are plateauing? Can we attribute this plateauing to clean energy, as the statement suggests? Let’s go to the data.

I clicked the link and found the data used in it, and here is what I found. Figure 1 shows global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels and land use change. Right away we see that emissions have gone up since 2020, but maybe we did plateau from about 2012 to 2022, and maybe it was from clean energy.

Problem 1. One has to ignore years associated with global pandemics. The 2020 dip is all COVID, and it took a few years to get back on track. There was also a smaller drop that started in 2015, followed by a slow climb back to 40 GtCO₂. What happened in 2015?

Figure 2 is emissions by fossil fuel type. The 2020 drop in coal and oil is easy to see, but notice that around 2015 there is a dip in coal use, while oil and gas continued to grow. The plateau from 2014 to 2015 is explained by the dip in coal use and a good bit of the drop after 2015, and the slow climb back is tied to coal use. What was happening was a transition in some places from coal to natural gas for electricity generation. The “plateau” was more about switching from coal to natural gas than about substituting with clean energy. Paragraph 1 of this article is at best misleading.

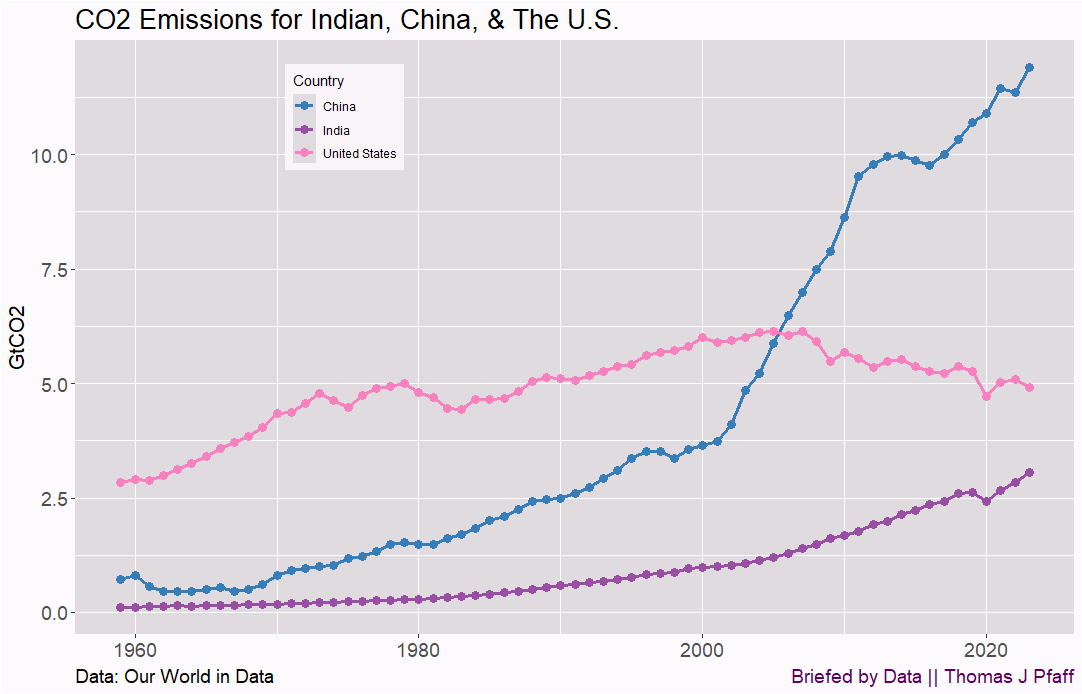

As you look at Figure 2, you might ask what went on with coal starting around 2000. Largely one country: China. Figure 3 shows the emissions of the three most populous countries. India now has more people than China, and it is close to a tie. While the U.S. is third, its population is less than 25% of either India or China.

As you can see, China’s emissions grew drastically starting in 2000, and much of that was burning coal. From 2012 to 2016, their coal use plateaued, contributing to the global emissions plateau.

A few other points about Figure 3. The U.S. has reduced emissions, but note that they are still out of proportion relative to populations in China and India. The U.S. still emits more per capita. Those on the left who are concerned about climate change also tend to be concerned about equity. What will happen if India increases its per capita energy use to match that of the U.S.? The problem is that right now, you can’t have energy equality without either more emissions or a reduced standard of living in wealthier countries. I'm not sure if clean energy can produce enough energy, either now or in the future.

Paragraph 1 is a lot of nonsense in this article. I did say two paragraphs.

This has contributed to a reassessment of likely climate outcomes this century, with the world now likely heading toward less than 3C warming by 2100 under current policies – compared to the 4C warming that seemed more plausible 15 years ago.

I’ll make this one shorter. Again, I clicked the link, which takes us to an academic publication (1/13/2025). First, the current policies assumption is really questionable, as predicting the future policies or behaviors of people is a fool’s game. Anyway, here is the abstract (bold mine):

The literature on current policy scenarios has become increasingly robust in recent years, with a growing consensus that the central estimate of 21st century warming is now likely below 3 °C. This reflects progress on both clean energy technologies and climate policies that has reduced the plausibility of high-emissions pathways, as well as a recognition that the higher end of emissions scenarios was never intended to represent the most likely no policy baseline outcome. However, it is difficult to fully preclude warming of 4 °C or more under a current policy world if there are continued positive emissions after 2100 or if carbon cycle feedbacks and climate sensitivity are on the high end of current estimates in the literature.

The second paragraph of this article seems a bit optimistic. The graph in the publication, Figure 4, is more concerning to me. The red bars represent 2100 warming under current policies. The central estimates haven’t changed much, and the second most recent paper has the red circle just below 3°C. This graph doesn't seem very hopeful to me, even though the bold portion of the error bars is a little lower.

I’ll say that putting optimistic or hopeful spins on energy and climate is just as bad as the doom and gloom spin. So far, clean energy is just adding to our desire for more energy use, and we still have substantial inequality in standards of living, which is tied to energy use around the world. Despite being a worthwhile and interesting scientific challenge, pinpointing the exact temperature of 2100 is not very practical.

Please share and like

Sharing and liking posts attracts new readers and boosts algorithm performance. I appreciate everything you do to support Briefed by Data.

Comments

Please let me know if you believe I expressed something incorrectly or misinterpreted the data. I'd rather know the truth and understand the world than be correct. I welcome comments and disagreement. We should all be forced to express our opinions and change our minds, but we should also know how to respectfully disagree and move on. Send me article ideas, feedback, or other thoughts at briefedbydata@substack.com.

Bio

I am a tenured mathematics professor at Ithaca College (PhD Math: Stochastic Processes, MS Applied Statistics, MS Math, BS Math, BS Exercise Science), and I consider myself an accidental academic (opinions are my own). I'm a gardener, drummer, rower, runner, inline skater, 46er, and R user. I’ve written the textbooks “R for College Mathematics and Statistics” and “Applied Calculus with R.” I welcome any collaborations.

I'd imagine per capita emissions and/or GDP emissions intensity will fall by a fair bit. But if we increase global growth from 2-3 percent per year to 3-5 percent per year due to the renewables boom, we would be in a vastly better position to deal with any climate adaptation challenges.